Editors’ note: This piece is from Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine’s fall 2023 issue, “How Do We Create Home in the Future? Reshaping the Way We Live in the Midst of Climate Crisis.”

At 3:30 a.m., a streetcar rings up on the corner of the Angola Cafe.

That night, the tides swept farther up on land than they ever had before, but we were all at Jardim do Morro.

We sprinted from one to another, pounding each other on the head with rubber hammers, thanking São João do Porto, even though none of us knew who he was.

And at that party in the garden, we also didn’t know that soon we would all be playing futebol underwater.

The day before, we had lain nauseous on boards in the ocean, feeling the Atlantic nudge us out and reel us back. We leapt up when the waves lurched forward, and were bowled over, somersaulting underwater like limp puppets.

We sensed but couldn’t say out loud the nervous truth: that all week, the waves had pushed with menace, no longer playful. We choked on salt and laughed, pretending not to notice the hostile bite of the water and the deep flash of ancient fear in our bellies.

The Wave had actually started days ago, kilometers away. While we danced oblivious on sweaty cobblestones, a long low thrum was traveling through the air in Serra do Gerês.

The rigid bones of the eucalypti stems snapped forward and bowed under The Wave. The Wave enveloped the pines, the boulders, and the cascades. It drowned the waterfalls, which instantly turned into spinning whirlpools under the surface. Then it continued on its way south, to Porto, on breezes tinged with mercury.

Meanwhile, we drank Super Bock and beat each other with hammers on that hill over the Douro.

***

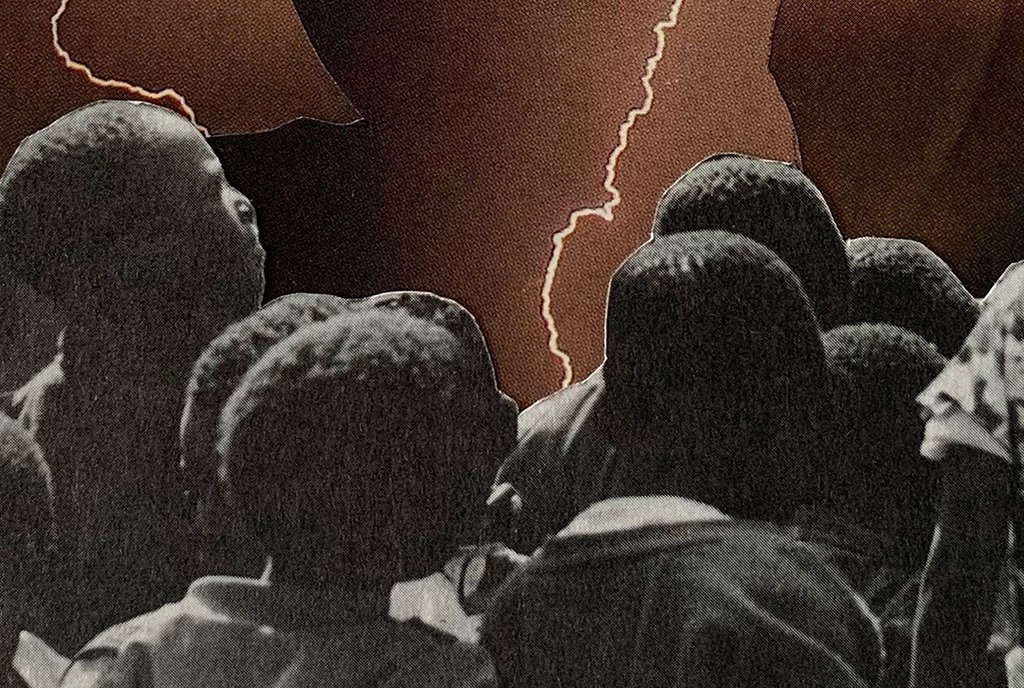

At first, it was scarcely noticeable. Water seeped through the grasses in Jardim do Morro until the toes of our bare feet were sticky with mud. When we looked up, we saw that the Ponte de Dom Luís I was covered in a thin blanket of water, the Douro swollen high enough to flow straight across the bridge.

Once the water was up to our ankles, slipping forward, we turned and tried to move the celebration to higher ground. But just those six inches disarmed strong, broad men, tossing them aside.

Then we were waist deep; and instead of flowing forward and toppling us, The Wave abruptly began to reverse, receding back into the Douro and inhaling us along with it.

We looked toward the halocline, where the mouth of the Douro met the Atlantic. What we saw there was not just a rogue wave or a wall of water—it was the whole ocean, lifted on its shoulders and blocking out the sky.

It inched just a reach higher, and the sun was gone.

Under the eclipse, we gaped and scrambled. We could only feel around us and imagine the world flipping and unfolding in the dark.

If we hadn’t been blinded, we would have seen that The Wave had left every crevice of the sea floor naked and exposed, with quivering mollusks—some that we would have recognized and others that were yet to be discovered—shivering against their first feel of air.

For a beat, The Wave stood upright—and all of us in the Jardim stared up at it in awe as it loomed over us, hammers still clenched in our fists.

Then, in one trembling crash, it fell to the ground and swallowed Porto.

***

It was like cliff diving in Gerês.

It’s a very precise moment—that fourth of a second right after you’ve been completely submerged, or perhaps right before the crown of your head is sucked under. In a few seconds, you will start thrashing and thrusting and propelling yourself upward, but for now, in this brief purgatory, you are suspended, weightless—not only in space but also in time.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The towering windows at São Bento station shattered, and water poured through them like a carafe emptying. Livraria Lello gulped, and the ink on the books evaporated. The ground, which had always been locked beneath us, suddenly seemed to feel The Wave and think that it, too, was liquid. It began sloshing and leaping up to try to touch the sky.

At first we were all in stasis, mannequins drifting unmoored through the membrane; then, around us, all that was anchored began to be ripped from their crevices, and we swam wildly away, flailing through the treacly womb in which we were encased—our arms and legs bent in ungodly angles by three kilometers of water trying to pin us down.

Ana drifted happily as the waves pressed on her throat chords, musing, “I got to have a big heartbreak with a French lover. It was wonderful. I’m so lucky. I’m so lucky.”

Inês had cried a river and drowned the whole world four times over, and wondered if this was her fault.

Thiago didn’t think he should admit it, but he was a bit relieved to not have to wonder about the future anymore.

Around them, chairs and fences and azulejo tiles swirled. Everything had gone horizontal, and we were living in a sideways world.

Really, the minute water seeped into the carpet rather than only the sink when we turned on the faucet, the world had ended. We’d always assumed we were attached, like placenta tethered to a belly, neatly divided; but The Wave sliced through the arrangement between our bodies and the milieu that had always cradled us. The orientation we depended on to rule the world ruptured, and we went tumbling out across the seismic movements of water under water.

Guillam marveled, in the oldest sense of the word, “How fantastic.”

***

On the last day of the world, how would you spend your time? We played futebol.

We pumped our legs up, but tonnes of water pressure forced our shins back down. When we kicked the ball, it twirled out and left a funnel of water in its wake. The water inside our bodies jostled against the water enveloping us, cushioning us like kidneys.

It was astonishing at first, but quickly, we situated ourselves again how we were most comfortable: insulated together, confidently dominating a small corner of something so much larger than us that we could not grasp it. We relaxed our limbs, reassuring ourselves that we were still exceptional. That was always how world-making went.

There were curious side effects: wrinkled fingertips, hair floating in nebulous clouds around our heads, bloated pale skin like that of corpses. The pressure at first made our eyeballs pop out, and we pressed them back in. We cracked eggs and watched the yolks float up above our heads.

We sat outside Aduela Taberna-Bar, on wicker chairs at the rattling tables, still lifting Porto tonics and caipirinhas to our mouths. The weight of the whole ocean pushed the glasses down, and we had to strain with shaking wrists to lift them. With each sip, more sea water rushed into the glasses and mixed with the limey fizz.

Do you look at the ocean and see it as one interconnected mother? Or do you see it as a million persons all shuddering together, each individual, rolling wave all furling and colliding alongside itself?

Movement wasn’t movement anymore—not like how it used to be. We lurched and slid across decades of sea in parallel heres and nows. Everything was in slow motion below the surface. Glee was subdued, and we all moved, graceful and lethargic, in extended soliloquies.

We couldn’t cut anymore; that had gone extinct with The Wave. As had clapping, snapping, whistling, and gasping. But we could spiral and rise.

There were no echoes on the seabed. Any words were carried off by the current the instant they left our lips, instead sending a dim sonar ring to the others’ ears, distorted and mottled and watery. Silence beat through our skulls, and when we widened our mouths to sing, we swallowed water. Our muted calls reverberated and bounced across the empty stage at the bottom of the ocean.

We moved in thick time. Remembrance folded and scrunched over itself, layering the now beside the past and future. We became used to each movement having happened while still yet to happen, to each wave carrying centuries before us on its back. We waded, our ankles sticky with weight, through the memory of histories we had never lived. Suddenly, we understood implicitly the mourning of ships that had traveled through us, and the joy of the birth of the world, when the whole planet had been sea. This, all on top of, within, under, and beside dim, milky memories of watching an anthropomorphized dinosaur walking through a red door on television as children and doubting its veracity as much as that of a memory of playing with egg-shaped dolls.

Without a sky, night and morning were a concept of the past. Now, time stretched perpetually forward in one long day for eternity. We drifted in one continuous consciousness, spilling from moment to moment without discretion.

Sometimes there was weather, which reminded us of that old world kept in our grandfathers’ shriveled muscles. When the water rustled angrily, and when it was calm and clear, it reminded us of the weightless, pressureless atmosphere that used to hold us, and how it used to be violent, too.

And we danced. The tissues in our bodies had crumpled to damp paper, but the water conducted us. Twirls expanded into billowing lunges, and we knocked about and inadvertently embraced. We toppled, fluid and long, like children play-pretending a grand ballet. But we weren’t embarrassed. When we tried to step, the currents dramatized us, lifting us to leap and pirouette across kilometers of empty ocean floor. Leagues apart, we could still move in sync, feeling each others’ push and pull, as if our fingers were interlocked. Space was above, not between, and the swell in one corner of the ocean made a wave in another.

And when we laughed, there was no sound, but streams of bubbles hissed out of the corners of our grins.