We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

The importance of expressing impact and gratitude in fundraising

The “one big thing” in fundraising is this: Advance the donor’s hero story. The previous article set in this series explored this in detail.

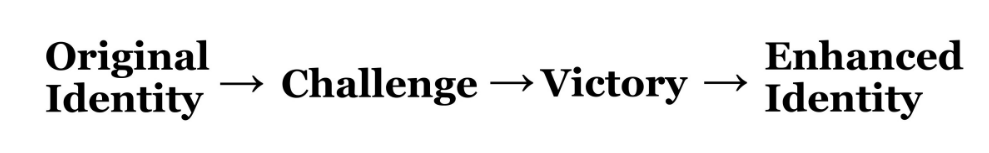

The universal hero story (monomyth) progresses through four steps:

The compelling donation experience includes these same steps. It starts by connecting with identity. This can come from the following:

- I am like them. (This is subjective similarity.)

- I am with them. (This is reciprocal alliances.)

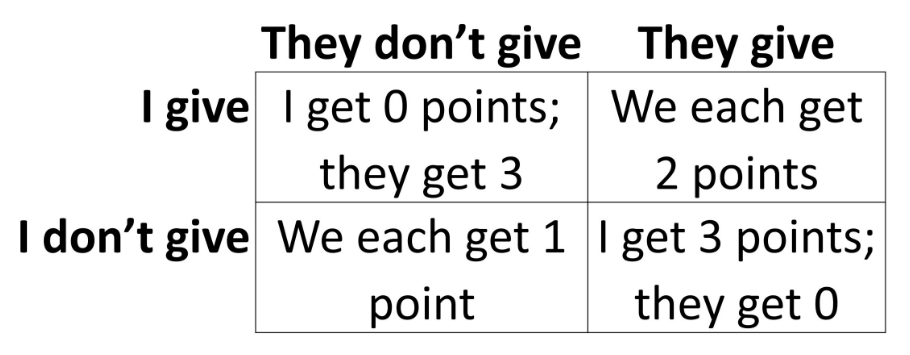

Biologists model reciprocal altruism with a game.[1] This primal-giving game can include simple alliances. But the game can do more. It can also include challenge and victory. It can include enhanced identity. It can include similarity and even heroism. But all this requires “leveling up” the simple game.

Impact

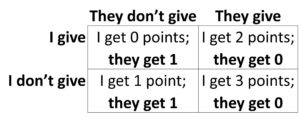

In the simplest primal-giving game, impact is fixed. And it’s identical. Two unrelated players face the same payoffs. Each must choose before knowing what the other will do. However, payback is possible because players can meet again. The payoffs are these:

Giving is costly. But it helps the other player more than it costs. If I give 1 point, the other player gains 2.

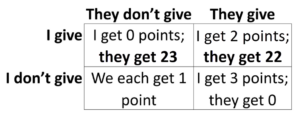

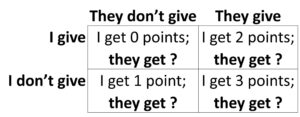

Now suppose the impact of my gift changes. The payoffs might instead become these:

Now, my gift has a higher impact. If I give 1 point, the other player gets 22 points. This might come from low cost. (The gift costs me $1. But a matching grant means the recipient gets $22.) Or it might come from high need. (The recipient’s benefit from $1 is 22 times my benefit from $1). How might this change alter gameplay?

Impact and gratitude

Impact is great. But in the game, or in nature, why would unrelated players even care? Let’s go back to the first law. In the primal game, giving has an unbreakable law:

Giving must be seen by partners who are able and willing to reciprocate.

Impact matters because it can lead to gratitude. Gratitude matters because it can lead to reciprocity.

Impact →

Gratitude →

Willingness to return a favor

A person expressing gratitude sends a signal. Gratitude signals their view of

- The impact of the gift

- The value of the relationship, and

- Their willingness to reciprocate.

This gameplay matches experimental research. Increasing impact works in donation experiments.[2] Expressing gratitude does, too.[3] Both work by supporting reciprocal social relationships.[4]

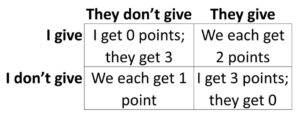

Impact encourages giving. Now consider the opposite. Suppose my gift has no impact. Payoffs become these:

Now, there is no reason to expect gratitude. My gift makes no impact. It does nothing to justify reciprocity. This gift makes no sense.

The hidden impact problem

What if I’m not sure of the other player’s payoff? I see the payoffs as these:

Should I give or not? It’s hard to know. There isn’t enough information. But with multiple rounds, I could test with a small gift.

Suppose I make a test gift and get silence. This signals no impact. It signals no willingness for reciprocity. Playing this game with this player makes no sense.

Suppose I make a test gift and get a report of impact and a meaningful expression of gratitude. I’ve learned something about the other player’s payoff. I’ve also received a reciprocity signal. Playing this game with this player does make sense.

The pro forma response

Not every response is meaningful. A “thank you” can be powerful.[5] But only if it signals gameplay. In the game, expressing desire for a social, helpful-reciprocity relationship is meaningful. Why? Because it signals gameplay. Not all gift responses do this.

Suppose I get a receipt that’s just stamped “thank you.” Or maybe only months later a “thank you” call comes. But it’s not from the charity. It’s from an outside telemarketing firm. The caller says things like,

- “This call may be monitored or recorded for quality assurance,” and

- “If you have any questions regarding your donation, please call member services.”

Do these signal a social, helpful-reciprocity relationship? Probably not.[6] Do these reveal information about my gift’s impact? Probably not. These don’t work in the game. So, it’s no surprise that testing finds they don’t work in real-world fundraising, either.[7]

The new donor problem

The hidden impact problem in the game often matches the new donor experience. They get a request. But they aren’t sure about the outcomes. So, they make a test gift.

How well do charities manage this hidden impact problem? Not well. About 70% of first-time donors to a charity never give to that charity again.[8] The game suggests why they are failing. Authentic signals of gift impact and gratitude work. Silence doesn’t.

How well does game theory match reality? In one large study, lapsed donors explained why they quit giving. The top three reasons related to the charity were these:

- “I feel that other causes are more deserving.” [Impact]

- They “did not acknowledge my support.” [Gratitude]

- They “did not inform me how my money had been used.”[9] [Impact]

In the primal game, impact is important. Gratitude is important. Without these, game strategy says, “Play with someone else.” In fundraising, the same rules apply.

Impact vs. reciprocity: The false gratitude problem

Gratitude reflects willingness to return a favor. Unless. Unless the signal is false. Suppose the other player expresses gratitude. But later, when they could easily return a favor, they don’t. The reciprocity signal was fake. Gratitude signaled future game play. But it was a false signal.

That’s how the game works. What about the real world? What happens when reciprocity fails? One study of over half a million donations to a public university gave an answer.[10] If the university failed to admit a donor’s child, the donor quit giving.

Logically, this shouldn’t have happened. Donors knew that donations were not part of the admissions process. But the emotion is hard to overcome. The university had a chance to help, and it didn’t. The relationship is broken. Only a fool gives to a player who won’t return a favor.

Impact vs. reciprocity: The charity crisis problem

The game is about predicting ability and willingness to return a favor. Impact can help by signaling higher willingness to return a favor. Unless. Unless it also signals lower ability to return a favor.

A charity may find that an organizational crisis appeal “works.” The charity is in trouble. The need is desperate. The gift will make a big impact. The appeal raises quick cash.

But this also cannibalizes the future large gift. It signals that the charity is unstable. This is now a less trustworthy player. They might leave the game anytime. Stable charities attract major gifts. Unstable charities don’t.

The conflict disappears if the crisis is not an organizational crisis. A stable charity can appeal on behalf of others in need. This doesn’t suggest that the charity is at risk. This is a crisis. But it’s not an organizational crisis.

The conflict also disappears if the charity faces an opportunity rather than a crisis. The gift still makes a big impact. But the charity isn’t signaling instability.

Impact vs. reciprocity: Weird results

Impact is important. But in the game, it’s important only as a reciprocity signal. Understanding this helps to explain some weird results.

In experiments, describing another player as needy increases giving to them.[11] Unless. Unless the other player had already shared money with the potential donor in a previous round. In that case, donors still give a lot. But they give the same, regardless of need.[12] The researchers explained,

“When the stranger is very willing to sacrifice [to help the potential donor], their need does not appear to matter.” [13]

Need can signal reciprocity willingness. But actual reciprocity behavior makes the signal redundant. The signal no longer matters.

Impact vs. reciprocity: Matching gift vs. lead gift

Reciprocity signals also help to explain the unusual power of lead gifts. The simple primal-giving game matches funding for a shared project, such as a neighborhood park. The project benefits the group. But there’s always a temptation not to give, hoping that others will take care of it.

How can a donor make a large gift in a way that encourages others to give, too? One approach is to promise a “matching” gift. A donor commits that for every dollar another donor gives, he will match it with his own gift. The impact of the other donor’s gift is doubled. This works.[14]

A different approach is to make a lead gift. A donor simply announces his large gift to help fund the project. Here’s the weird thing. This also works.[15]

In fact, an announcement of a lead gift works better than an announcement of a matching gift of the same size. This is true in both real-world fundraising and lab experiments.[16]

What’s going on?

The promise of a match can help. But it creates no reciprocity obligation. It’s contingent. It says, “If you don’t give, I won’t either.”

The lead gift is different. I lead with a gift that helps you (or something you care about). I give, hoping for your response. If you don’t give, you violate reciprocity norms. I gave; you left me holding the bag. Everyone can see that you are a bad partner.

The promise of a match helps. But it sends a contingent signal. A lead gift helps more. It sends a stronger signal.

Adding similarity to the game

So far, the game has included only unrelated players. In that version, I care about the other player only to the extent that it affects me. Things change if I feel that the other player is like me.

This returns us to Hamilton’s simple math.[17] I give when

My Cost < (Their Benefit X Our Similarity).

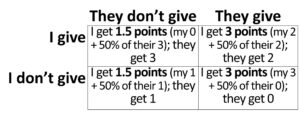

In the original game, both players faced these payoffs.

Now, suppose I treat the other player as a brother. This equates to 50% similarity. Based on Hamilton’s genetic math, I now count 50% of their benefit. My payoffs change to these:

Before, giving was costly for me. Now, it’s not. But it still makes the world a better place. More giving still means more total points. Adding similarity makes giving more attractive.

It also makes impact more important. With unrelated players, impact is important only indirectly. It affects the game only through reciprocity. But with related players, it also has a direct effect. It directly benefits someone who is like me.

Conclusion

Compelling fundraising story starts with identity. It starts by identifying with another. Identifying with others can come from two sources:

- I am like them. (This is subjective similarity.)

- I am with them. (This is reciprocal alliances.)

In natural selection, giving has the same two origins: similarity and reciprocal alliances. The expanded game models both.

We’ve taken a deep dive into natural selection principles. We’ve come back with story principles. The biologist’s game and the storyteller’s game start at the same place. They both start with identity.

But for transformational gifts we need to “level up” the game once more. It’s time to move beyond the natural origins of the donation. It’s time to explore the natural origins of the heroic donation.

Footnotes:

[1] Boyd, R. (1988). Is the repeated prisoner’s dilemma a good model of reciprocal altruism? Ethology and Sociobiology, 9(2-4), 211-222.

[2] See, e.g., Shehu, E., Clement, M., Winterich, K., & Langmaack, A. C. (2017). “You saved a life”: How past donation use increases donor reactivation via impact and warm glow. In A. Gneezy, V. Griskevicius, and P. Williams (Eds.), NA – Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 45). Association for Consumer Research, p. 270-275. p. 272. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v45/acr_vol45_1024372.pdf (“past donation use increases the perceived donation impact, then induces warm glow which translates into a higher intention to donate in future”)

[3] See, e.g., Andreoni, J., & Serra-Garcia, M. (2021). The pledging puzzle: How can revocable promises increase charitable giving? Management Science, 67(10), 5969-6627, p. 5969 (“If expressions of gratitude are then targeted to individuals who select into pledges, reneging can be significantly reduced and contributions significantly increased.”) Or, for pro-social behaviors more generally, see the review in McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127, 249-266.

[4] Sznycer, D., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2019). The ecological rationality of helping others: Potential helpers integrate cues of recipients’ need and willingness to sacrifice. Evolution and Human Behavior, 40(1), 34-45. See also, Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 946-955.

[5] Andreoni, J., & Serra-Garcia, M. (2021). The pledging puzzle: How can revocable promises increase charitable giving? Management Science, 67(10), 5969-6627.

[6] Suppose to save time a newlywed couple hired a telemarketing firm to contact each person who gave a wedding gift. The hired telemarketer says, “thank you for your wedding gift.” Technically speaking, this would qualify as a “thank you” or “donor acknowledgement.” However, it certainly does not express either impact of the gift or a willingness for a helpful reciprocity social relationship. The intuitive understanding of the inappropriateness of such a “thank you” in this social context also applies to the social context of a charitable giving relationship.

[7] An experiment tested this type of “worst case” scenario, where the calls from an outside telemarketing firm were made 5-7 months after the donation and included variations of these phrases. Although donations were still higher among those who actually received the calls than those who didn’t, the overall effect for being on the list of those who were at risk of potentially being contacted in the experiment was not statistically significant. See, Samek, A. & Longfield, C. (2019, April 13). Do thank-you calls increase charitable giving? Expert forecasts and field experimental evidence. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3371327

[8] https://bloomerang.co/retention (“‘Over 70% of people that we recruit into organizations never come back and make another gift, so we’re caught on this treadmill where we have to spend lots of money on acquisition which most nonprofits lose money on anyway, just to stand still.’ Professor Adrian Sargeant”); See also Levis, B., Miller, B., & Williams, C. (2019, March 5). 2019 fundraising effectiveness survey report. (Reporting 20% retention of new donors in the first 12 months.)

[9] Sargeant, A. (2001). Managing donor defection: Why should donors stop giving? New Directions for Philanthropic Fundraising, 2001(32), 59-74. p. 64. table 4.1. (I omit non-charity causes such as donor finances, death, relocation, or inability to remember making the initial gift. However, this last reason may also relate to charity’s lack of impact reporting or gratitude expression.)

[10] See, Meer, J., & Rosen, H. S. (2009). Altruism and the child cycle of alumni donations. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1(1), 258-286.

[11] “In the low need condition, the stranger is living a normal, happy life. In the high need condition, the stranger has experienced costly medical difficulties recently that are making completing school difficult.” Sznycer, D., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2019). The ecological rationality of helping others: Potential helpers integrate cues of recipients’ need and willingness to sacrifice. Evolution and Human Behavior, 40(1), 34-45. p. 42.

[12] Id. p. 40. Figure 2.

[13] Id. p. 40.

[14] Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2003). Rebate versus matching: Does how we subsidize charitable contributions matter? Journal of Public Economics, 87(3-4), 681-701; Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2006). Subsidizing charitable giving with rebates or matching: Further laboratory evidence. Southern Economic Journal, 72(4), 794-807; Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Subsidizing charitable contributions: a natural field experiment comparing matching and rebate subsidies. Experimental Economics, 11(3), 234-252; Karlan, D., List, J. A., & Shafir, E. (2011). Small matches and charitable giving: Evidence from a natural field experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 95(5-6), 344-350.

[15] Ebeling, F., Feldhaus, C., & Fendrich, J. (2017). A field experiment on the impact of a prior donor’s social status on subsequent charitable giving. Journal of Economic Psychology, 61, 124-133; Kubo, T., Shoji, Y., Tsuge, T., & Kuriyama, K. (2018). Voluntary contributions to hiking trail maintenance: Evidence from a field experiment in a national park, Japan. Ecological Economics, 144, 124-128.

[16] Epperson, R., & Reif, C. (2019). Matching subsidies and voluntary contributions: A review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(5), 1578-1601; Huck, S., & Rasul, I. (2011). Matched fundraising: Evidence from a natural field experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 95(5-6), 351-362; Huck, S., Rasul, I., & Shephard, A. (2015). Comparing charitable fundraising schemes: Evidence from a natural field experiment and a structural model. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(2), 326-69; Rondeau, D., & List, J. A. (2008). Matching and challenge gifts to charity: Evidence from laboratory and natural field experiments. Experimental Economics, 11(3), 253-267.

[17] Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7(1), 17-52.

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- How transactional donor relationships kill generosity

- Dr. James explains the power of giving: why leading with a gift always wins

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!