(Illustration by Taslim van Hattum)

(Illustration by Taslim van Hattum)

As an advocacy strategy consultant and evaluator for the last two decades, I’ve supported many foundations in thinking about what it takes to win a particular policy or system change. What will it take to expand Medicaid eligibility in states? How can we improve preschool access and quality? Foundations have come at these and similar questions using different theories of how policy change occurs, but the end goal is always the same: getting to “the win,” whether that be a policy change, increased funding, or adjusted priorities.

My perspective shifted on what the end goal of advocacy strategies should be, while working with The California Endowment (TCE) on their 10-year Building Healthy Communities (BHC) initiative. TCE has funded policy advocacy efforts since its inception in 1996, but while the foundation had long considered people power to be an important driver of the work to achieve policy and systems change wins, during BHC, the ultimate goal that TCE and its partners sought to achieve became building people power. This shift required TCE to rethink its role as an advocacy funder in supporting people power, from who it funded and how to for what purpose. Witnessing the transformative impacts of these changes, I became a strong supporter of this new approach to funding social change advocacy.

Why should advocacy funders pay attention to power?

People power means that people who are most impacted by policies and systems have the power to define and secure the changes they want for themselves and their communities. This power can build over time as communities organize and advocate for the changes they seek and then use what they learn and gain from the process of winning (or losing) to continue advocating for more wins.

Advocacy strategies that build people power are more likely to sustain, and to further build on, wins after they occur. After all, philanthropy is littered with examples of policy wins that were attacked or rolled back because there was no organized base with power to protect those wins. When it came to BHC, however, an evaluation by the Center for Evaluation Innovation and one by the Center for Outcomes Research and Education revealed that many wins achieved over the initiative’s 10 years actually related to and built on one another over time: As communities achieved policy or systems change wins (or experienced losses), they used their expanding power to advocate for a next win, and then a next, working cumulatively toward long-term transformational goals.

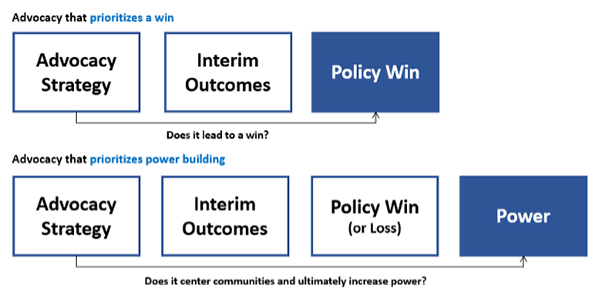

Of course, “winning” should still be an important goal of all advocacy strategies. Changing the way policies and systems are structured, run, and resourced can obviously be transformational. But making winning the singular focus of advocacy efforts—which many of us have done for years—can miss the opportunity to produce more fundamental and lasting change.

Policy or systems change wins (or losses) should be viewed as interim steps toward the end goal of building people power:

What do advocacy ecosystems need to build people power?

Much has already been said and written about how funders can support advocacy that builds power. It is clear that philanthropy should support more community organizing, which has as its central purpose building people power. Organizing groups offer community members a political home: a place to build community, a place to envision a different future, and a place to act collectively to build power. Historically, philanthropy has not made it a priority to ensure these groups have the long-term resources they need to scale up and sustain their work, and that needs to change.

However, just providing organizing groups with more funding is not enough. Organizers need the support of other actors—professional advocates, think tanks and policy shops, researchers, communications firms, funders, evaluators, and others—to recognize the critical role of organizing and to share the long-term goal of building people power. Working together, these entities make up the advocacy ecosystem.

In ecosystems equipped to achieve their policy or system-change goals and build people power, organizers and the communities they work with are not only included, but they drive advocacy efforts. The central role of communities and community organizers in building people power requires advocacy ecosystems to move from focusing on wins to focusing on building power:

- FROM a policy or systems change “win” is the goal TO a “win” is a means—Power is the goal.

- FROM policy solutions being informed by community TO policy solutions being developed and informed by impacted communities.

- FROM advocacy done on behalf of communities TO advocacy done by and with impacted communities.

- FROM the drivers of change being pundits and policy professionals TO an authentic organized base being the primary driver of change.

- FROM strategy based on an analysis driven by politics and windows of opportunity TO strategy based on a shared analysis grounded in root causes of inequities.

- FROM the advocacy campaign is the strategy and organizing is the tactic used to achieve a win TO organizing is the strategy and advocacy is the tactic through which power is built.

- FROM the work organized in a series of time-bound campaigns that may or may not add up TO the work being continuous and iterative and a series of campaigns expands the power and influence of participants over time.

- FROM specific and time-bound capacity building focused on the “win” TO advocacy and campaigns being a leadership development opportunity to build power.

- FROM others drive narratives about community TO impacted communities drive narratives that tell their stories and challenge dominant frames

Currently, professional policy advocacy organizations and policy shops hold the most power and generally take a lead role in the advocacy process. They conduct policy analyses and research, lead the development of policy agendas and campaigns, staff formal collaborations, and hold inside relationships with decision-makers. Usually established 501(c)3 organizations with relationships to funders, they are regular recipients of advocacy-related funding.

In contrast, organizers and the communities impacted by the policies or systems that advocates work on tend to have comparatively less power (in part, because philanthropy has not historically supported organizing groups). In addition, the advocacy actors who hold the most power in advocacy ecosystems have not shared it. As a result, professional advocacy organizations may mobilize communities to share their experiences or stories with decision-makers, but those communities have little say in developing the policy agenda. Instead, they are deployed to support an agenda after it has already been decided.

How can funders help to shift power in advocacy ecosystems?

In addition to supporting community organizing groups, funders can strengthen power-building efforts by encouraging non-organizing advocacy actors (including funders themselves) to cede power and change how they relate to communities and organizers. In advocacy ecosystems where power traditionally has been held by non-organizing actors, advocacy funders can leverage their dollars and their influence to help shift these dynamics.

Some foundations have been pursuing this strategy with success. In two recent projects across nine states, for example, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded efforts to change early how power was held in childhood advocacy ecosystems. In these states, statewide policy advocacy organizations had been connecting to parents by conducting research to learn about parent experiences and mobilizing parents to support particular policy goals or campaigns, which left parents shut out of the process of forming policy advocacy agendas and strategies. The goal was to shift power toward community-based organizations that worked directly with parents of young children. Our evaluation revealed that most states achieved this goal and did so by making structural changes in the composition of their ecosystems (who participates) and in the connections and power dynamics between partners. To engage parents directly, state advocates either hired parent organizers or built or strengthened partnerships with existing parent-focused organizers or organizations, often by passing RWJF funding directly to them.

Another example of non-organizing actors shifting their relationship to communities comes from the Budget Power Project in California. Supported by The California Endowment, Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, James Irvine Foundation, Blue Shield of California Foundation, and others, the California Budget and Policy Center is partnering with power-building organizations Catalyst California and the Million Voters Project to support community-based organizations in leading advocacy on public budgeting processes, particularly at the local level. It is shifting the relationship of a high-profile statewide policy shop to be in service of power building in California.

Takeaways for Advocacy Funders:

Building on the experience of TCE and other funders that have supported power-building, the lessons here for advocacy funders are three-fold:

- To advance equity and justice, the end goal of advocacy efforts should be building people power.

- Advocacy ecosystems need sufficient organizing capacity to build people power.

- Building people power requires that non-organizing actors in the advocacy ecosystem—funders included—cede power to organizers and align around this shared goal.

While the first two lessons are gaining a stronger toehold in philanthropy, the third is not getting through to many foundation leaders. Foundations still have a lot to learn about how to support this work effectively and cede power themselves. Other non-organizing advocacy actors—all with critical roles to play in building people power—face similar challenges. If we do not learn to “stand up and step back,” professional advocates, policy analysts, researchers, communicators, and evaluation consultants like me can hinder progress toward achieving the very goals for which we advocate.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Julia Coffman.