What would it look like for rural civic infrastructure to thrive, not just survive, in the 21st century? This is a question animating much of our work in East Texas, where a local family foundation (T.L.L. Temple) and a community development financial institution (Communities Unlimited) are teaming to develop bottom-up structural solutions to building rural capacity.

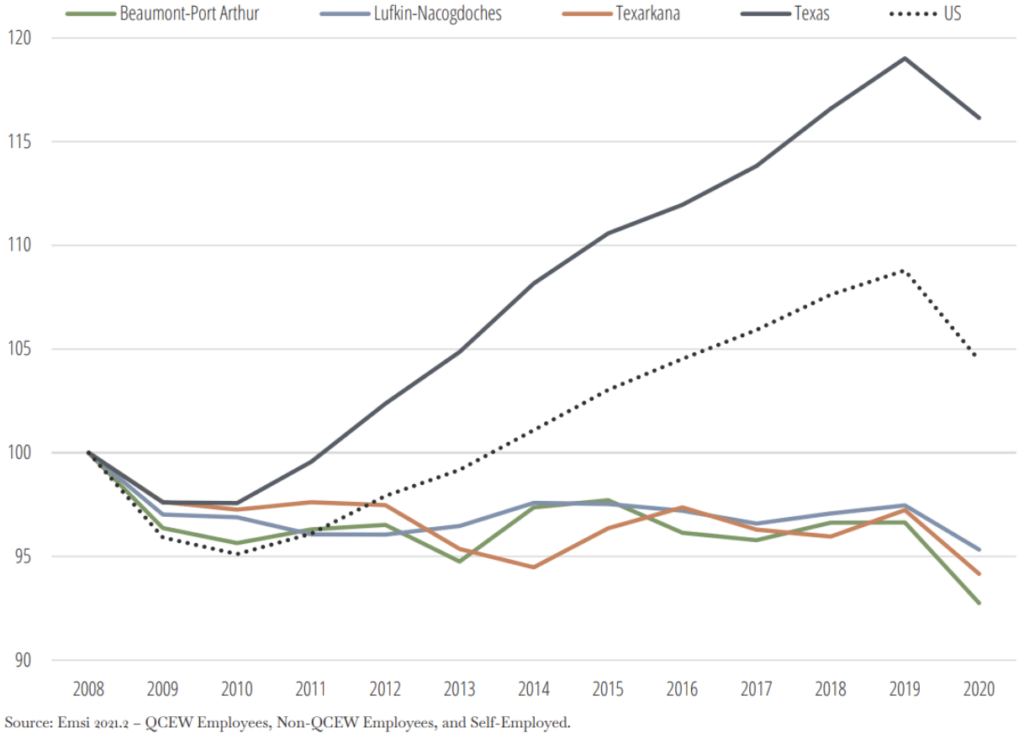

When we talk about economic development in East Texas, we often like to start with the figure below, which comes from a T.L.L. Temple Foundation report and shows 13 years of comparative employment data for the United States, the state of Texas, and three East Texas regions.

The graph has a clarifying quality, disabusing any suggestion that our regions (represented by the green, blue, and orange lines) are on the right track. Despite press accounts about the past decade’s so-called Texas Miracle, rural East Texas employment is still lower than where it was more than a decade ago.

East Texas is a sprawling, largely rural region consisting of 38 counties and over 1.9 million people. Our communities are rich in history and diversity, including sizable Black populations in urban hubs like Texarkana and Beaumont, a rapidly growing Latinx population, and the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe.1 Unfortunately, these distinctive communities share a common feature of often being excluded from the benefits of economic development.

What’s needed is what we like to call a “long lift”…that simultaneously addresses immediate challenges…while building civic scaffolding.

Combined with other data that reveal our rural communities to be sicker and poorer than the state and nation, these facts have by necessity moved the search for solutions from activities and projects to systems and structures.

The barriers to change are real and persistent. Efforts to initiate rural revitalization strain institutions and distressed communities. Exhaustion and exasperation often lead to a sense of: “Not another thing to manage.”

The needs and aspirations of local rural communities should always be at the forefront, but those of us engaged in place-based rural development know that we cannot load additional responsibilities onto civic infrastructures that already struggle to keep pace. Current rural civic infrastructure often operates under a default scarcity mentality because it was designed for a different demographic, social, economic, and technological context, and is no longer fit for purpose. As these seismic changes accelerate, too many rural places are caught in a vicious circle of inadequate capacity, in a defensive posture trying to hold on, rather than progressing toward rural prosperity and thriving rural communities.

Re-Envisioning Rural Capacity Building: The “Long Lift”

What’s needed is what we like to call a “long lift”—an integrated effort that simultaneously addresses immediate challenges and barriers while building the civic scaffolding that can sustain gains over time. However, there is uncertainty about who can step forward and how they can address this rural capacity gap. Federal and state agencies have identified the challenge and have launched initiatives. While these efforts are vital and welcome, they take time to set up, have been relatively limited in geographic scope, and are compartmentalized by program sectors.

Rural philanthropy, we believe, can make a positive difference. Unfortunately, philanthropy is disproportionately underinvested in many rural areas, and the sector has not yet coalesced around standard rural-focused methods, tools, and models. Borrowing language from recent findings on rural entrepreneurship, rural philanthropy should be understood as “a distinct phenomenon worthy of distinct focus.”

So how can rural philanthropy meet this moment? As has been described widely, federal infrastructure funding, allocated to historically underserved communities across the United States, provides an opening. Yet federal funding allocations are necessary but not sufficient to create meaningful changes in the lives of families. To access this funding, rural communities need to build and mobilize inclusive organizing structures and financing mechanisms. This is one place where philanthropic support can be helpful.

In rural East Texas we have a pilot model to get started. Attempting to tackle the rural capacity challenge head on, our two organizations—the T.L.L. Temple Foundation and Communities Unlimited—partnered to launch ConnectRURAL (Regions Underserved Resources Available Lineup), a five-year initiative to bolster civic infrastructure across rural East Texas. The model maps onto clear and well-documented factors driving rural capacity gaps: staffing, technical expertise, and resources. For those across the country serving rural areas who have requested more details about bringing a similar model to their communities, this article hopefully offers some insight into what we see as fundamental, start-up components.

A Regional Pilot Approach

Aligned with the resurgence of regional place-based problem-solving and reflecting the approach of new federal place-based policies and programs, ConnectRURAL aims to work at a regional scale.

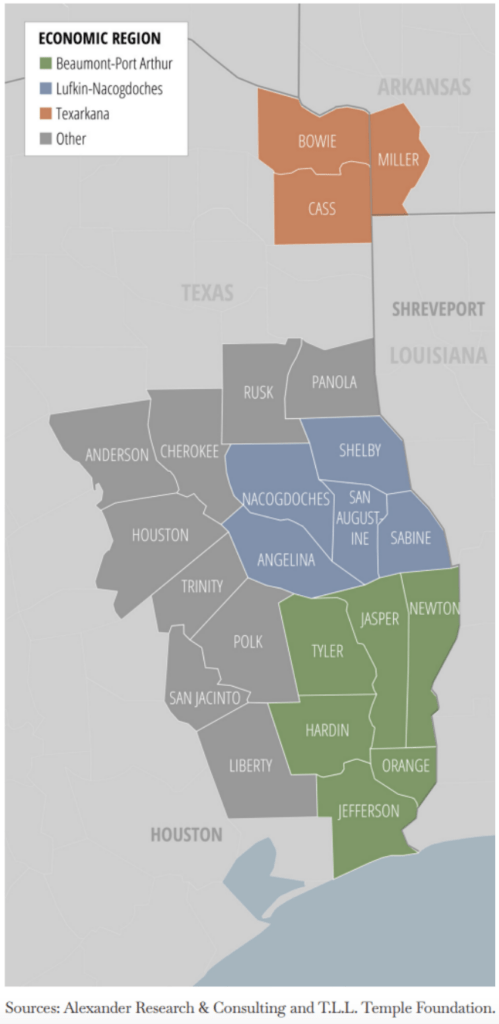

The foundation started by defining and analyzing coherent rural regions in East Texas, based on the Rural East Texas Economic Opportunity Analysis developed through a partnership with Alexander Research & Consulting. This report analyzed our foundation’s rural service area—integrating job density, commuting, and industry and occupational data into defining three coherent regions.

Rural communities run on trust….Effective capacity building initiatives must reflect how rural places work.

Report findings are already informing local and regional decision-making processes—from improving school district strategic planning, to aligning coordination of career and technical education programs, to spurring investment into the largest commercial driver’s examination and training center in the state of Texas. The definitions of these rural regions will also guide the location and boundaries of three development hubs. These multi-county regional hubs—colored orange, blue, and green on the map below—provide the unit or level of action for pursuing regional capacity building.

Defining the Model

While the norm is to offer rural areas technical assistance via temporary fly-in or drive-by consultants or by placing information on a website, rural communities run on trust built through long-term relationships. Effective capacity building initiatives must reflect how rural places work.

One step we believe is essential—and lies at the core of the model—is the creation of a new staff position at Communities Unlimited: the community resource manager. These managers are skilled generalists who live and are rooted in each defined region across East Texas. They will collaborate with local elected and civic leaders to identify needs, develop action plans, provide grant writing assistance, coordinate next steps, and be available to do whatever is necessary to keep local momentum moving forward.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Community resource managers will seek to link bottom-up local action with technical experience.

Through this process, these managers will aim to establish trust and serve as a reliable bridge, helping communities access different types of specialized expertise needed to support a pipeline of successful proposals and projects. They will be matchmakers, connecting local leaders to the suite of technical assistance and financing tools provided by Communities Unlimited.

Communities Unlimited maintains a multistate network of technical assistance expertise across a range of essential infrastructure sectors—including rural water systems, broadband, entrepreneurship, small business lending, and community sustainability. This range of services reflects the reality that rural communities are not siloed—they are taking on a multitude of challenges all at once, including broadband, water, energy, and economic development. The idea, therefore, is to be intentionally multisectoral and versatile to be able to move potential ideas to action and support rural renewal at scale.

The community resource managers will seek to link bottom-up local action with technical experience, helping form and connect coalitions to accelerate changes at a previously unattainable scale. ConnectRURAL will also seek to mitigate a common barrier to securing federal grants by creating a designated funding mechanism for rural communities, so they can access resources to meet required cost-sharing and matching requirements.

The foundation has committed $400,000 to Communities Unlimited to use as rapid access capital for this purpose. These geographically dedicated matching dollars will be complemented by emerging sector-specific pooled philanthropic funding, such as the recently launched Texas Wellspring Fund for resilient water systems. Together, place-based matching and expanded pooled funding mechanisms will help rural communities act on the innovative ideas and determination that they have rather than be stopped by matching funds that they lack.

How Will We Know If the Pilot Works?

Having just launched this initiative in 2022, we have much to learn. Right now, the focus is on solving tangible rural challenges.

Our experience is that local leaders are seeking to execute on the next best step and make practical progress. There is an opportunity to develop new, complementary, and interconnected civic infrastructure where gaps exist, to identify and build minimum viable rural ecosystems.

Launching essential institutions that were previously absent from the rural East Texas ecosystem, such as two CDFIs, has been instrumental in raising the ceiling on what is possible. These CDFIs are already having significant regional impacts, supporting previously neglected entrepreneurs and small businesses. Working with empowered, high-capacity regional institutions, thousands of community stakeholders are challenging the lack of essential services, such as broadband, and convening summits to develop solutions to physical infrastructure limitations, like water systems. These efforts are building positive momentum and a buzz that change is possible.

A few questions serve as bellwether indicators and guides for whether we are on the right track.

For one, are communities, particularly those who have been most isolated and left behind, increasing engagement through our development hubs? Initial evidence is positive, as community resource managers have been overwhelmed with demand for local outreach and project planning.

Is this engagement building bridges between rural communities starved for resources and transformational federal funding opportunities? Again, initial evidence is that multiple rural communities across each region are working, many for the first time in years or decades, to become application-ready and to submit competitive funding proposals.

Finally, are philanthropic investments attracting complementary partnerships and funding? We anticipate that as rural areas improve their planning and management acuity, these communities will become decipherable, navigable, and less “risky” for state and national funders interested in rural equity, both private and public. Initial evidence points to emerging partnerships with key federal partners like Rural Development at the US Department of Agriculture and with other private foundations.

All of that said: people in East Texas know that this will be a long lift, and we must be persistent. Future decisions will require adapting staffing structures to regional demands and developing a measurement system to quantify both the process measures and downstream outcomes.

Ultimately, making the case for this approach requires demonstrating the return in community impact. We expect that this return will be high and motivate a new way forward for rural philanthropy.

Until we know for sure, we will learn by doing. The basic model is action-oriented and appropriate to meet the enormous opportunities and challenges in rural communities: locally embedded community coordination and facilitation has been plugged into distributed networks of technical assistance and pooled funding mechanisms.

This is the start of an all-in effort to enable a rural civic infrastructure that will thrive, not just survive. We welcome further ideas, innovation, and collaboration to meet the moment and keep the momentum moving forward for rural communities across the country.

Notes:

- In keeping with NPQ style, we use “Latinx” here. However, in East Texas, Latinx community leaders more commonly refer to themselves as “Hispanic” or “Latino.”