These days, the threat of gentrification looms large in many US cities, as has been widely covered at NPQ. The position of food co-ops in this mix can be ambiguous. On one hand, community-owned food co-ops can be a powerful strategy to assert community control over local food and avoid resident displacement. Yet food co-ops are also sometimes criticized as being potential agents of gentrification.

In September, at this year’s Up & Coming Food Co-op Conference, participants addressed the challenge of gentrification head-on in a session called “Are Food Co-ops a Gentrifying Force?” Darnell Adams, a board member of Food Co-op Initiative (one of the organizations cohosting the conference), moderated the conversation. Participants on the panel included Steve Cooke, general manager of Friendly City Food Co-op in Harrisonburg, VA; Raynardo Williams, general manager of Seward Community Co-op in Minneapolis; and Jamila Medley, a founder of the Philadelphia Area Cooperative Alliance.

The threat of gentrification looms large in many US cities….The position of food co-ops in this mix can be ambiguous.

Adams defined gentrification as the “influx of more affluent residents and businesses [which] often causes the displacement of people and businesses that have already been there.” At one point in the conversation, Adams asked if the mere fact of food co-op success might unwittingly create a situation that causes gentrification. The consensus: no, provided that an intentional approach to community building was employed and solidarity was placed at the center of co-op organizing. Each participant shared their story of how they embodied this approach to prevent the gentrification of the communities they served.

A Food Co-op Example from the Shenandoah Valley

Friendly City, as noted above, is based in Harrisonburg, a college town of a little over 50,000 people located in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Cooke said that after the co-op opened in 2011, it quickly became financially successful and was praised for doing “everything right.” But some things were not right.

The store, Cooke noted, was sited in a largely African American neighborhood, one that historically had, like many Black communities, seen several square blocks razed in the fifties and sixties in the name of urban renewal. This history might not have been top of mind for many of the co-op’s primarily White organizers. But that community memory was very much alive for many local Black residents.

Indeed, for many Black community members, the co-op was seen as just another outside White-owned grocery store, an impression that was not inaccurate. After all, the organizing group was largely White, and the store was not designed with the local Black community’s needs in mind.

Cooke said that “when members were recruited—the founding organizers probably thought by putting the store in this area…it would be a great thing,” which would address the neighborhood’s lack of groceries “with local natural, organic, shade-grown, fair-trade food.” But when residents saw that cucumbers cost two dollars, while the price at Walmart was a third as much, they were not impressed.

Cooke recalled a food equity meeting he attended in 2015 that was held just three blocks away from the co-op. When the meeting facilitator asked residents what the community needed, the answer was a “community grocery store.” Clearly, Cooke realized, the store was seen as being outside the community, not a part of it.

In response to that meeting, Cooke said, the co-op has sought to address past shortfalls by hiring more staff of color, expanding programs that serve low-income residents (such as operating a match program that reduces produce prices for purchases made with food stamps), changing the product mix to meet community needs, and hosting exhibits in the store that highlight the Black community’s neighborhood history, including educating customers about the displacement of Black businesses and residents that resulted from urban renewal. The work of inclusion, he added, was ongoing.

A Broader Challenge

Cooke observed that Friendly City’s case is hardly unique. As he explained, economic reasons, such as the desire to obtain buildings for a lower rent or better access to space or parking, have led “a lot of co-ops…to locate in lower-income communities.” This might help improve a co-op’s financial numbers, but an additional consequence is that “some, unconsciously or not, have had a White savior ethic to provide food in that community that is seen through a lens of healthy food.”

One step to ensure that food co-ops empower the community rather than serve as agents of displacement…is to build in partnership with the community.

Williams concurred, noting that when Seward Co-op of Minneapolis, the city’s oldest continually operating food co-op (founded in 1972), was seeking to open a second location, co-op leaders initially assumed that they “could take the branding and plop it into a new community.” At an early community meeting, co-op leaders touted the fact that 14 percent of staff were people of color, suggesting that this figure showed that the co-op was a leader in racial diversity, even though citywide the percentage of residents who were people of color was much higher—nearly 40 percent. The co-op, Williams said, “was seeing itself as a savior.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Medley said she witnessed a similar dynamic in Philadelphia. “One of the things that was very present as these stores were in their formations: they were almost exclusively founded by White people in neighborhoods that were not primarily White….One of the things I saw and experienced is that these lovely well-intentioned White folks often were new to the community. They were doing their co-op organizing in a way that was meeting their [own] needs.”

“Be a part of where you are, and the people who are there with you can help create the environment, the culture, the ‘we’…you want to create.”

Organizing with Intention

One step to ensure that food co-ops empower the community rather than serve as agents of displacement, noted Medley, is to build in partnership with the community. This fundamentally means building personal relationships with those who live in the service areas. The organizing imperative, she added, is to “be a part of where you are, and the people who are there with you can help create the environment, the culture, the ‘we’ for the kind of story that you want to create.”

Seward, after a less-than-auspicious start in the organizing of its second store, recalibrated to do that. Part of this story, as Susan Pagani wrote about years ago for Civil Eats, was to hire LaDonna Sanders-Redmond—now the co-op board’s president—to be a community organizer and go door-to-door. Williams noted that “getting out and getting to know what the community wants is very important.”

Williams insisted that three principles that Seward followed were particularly important: transparency, accountability, and follow-through. “When the community said, ‘We want to see these, that these jobs need to be in the community, that we need to carry specific products,’ we had to follow through.”

Seward’s store opened in 2015 with Williams, who is African American and now is general manager of the entire co-op, serving as the store’s first manager. By 2016, according to Pagani, the percentage of staff of color in the co-op had climbed from 14 percent to 36 percent. At the new store in the Friendship neighborhood, 56 percent of staff were people of color. Not only that but 55 percent of the store’s staff were from the local Bryant zip code.

This balance was achieved intentionally and methodically. A key tactic in hiring staff of color was to have a job fair in partnership with Black and Latinx media and community organizations instead of relying on informal job networks, which were primarily White. According to Pagani, nearly 100 people were hired because of this effort.

More Than a Grocery Store

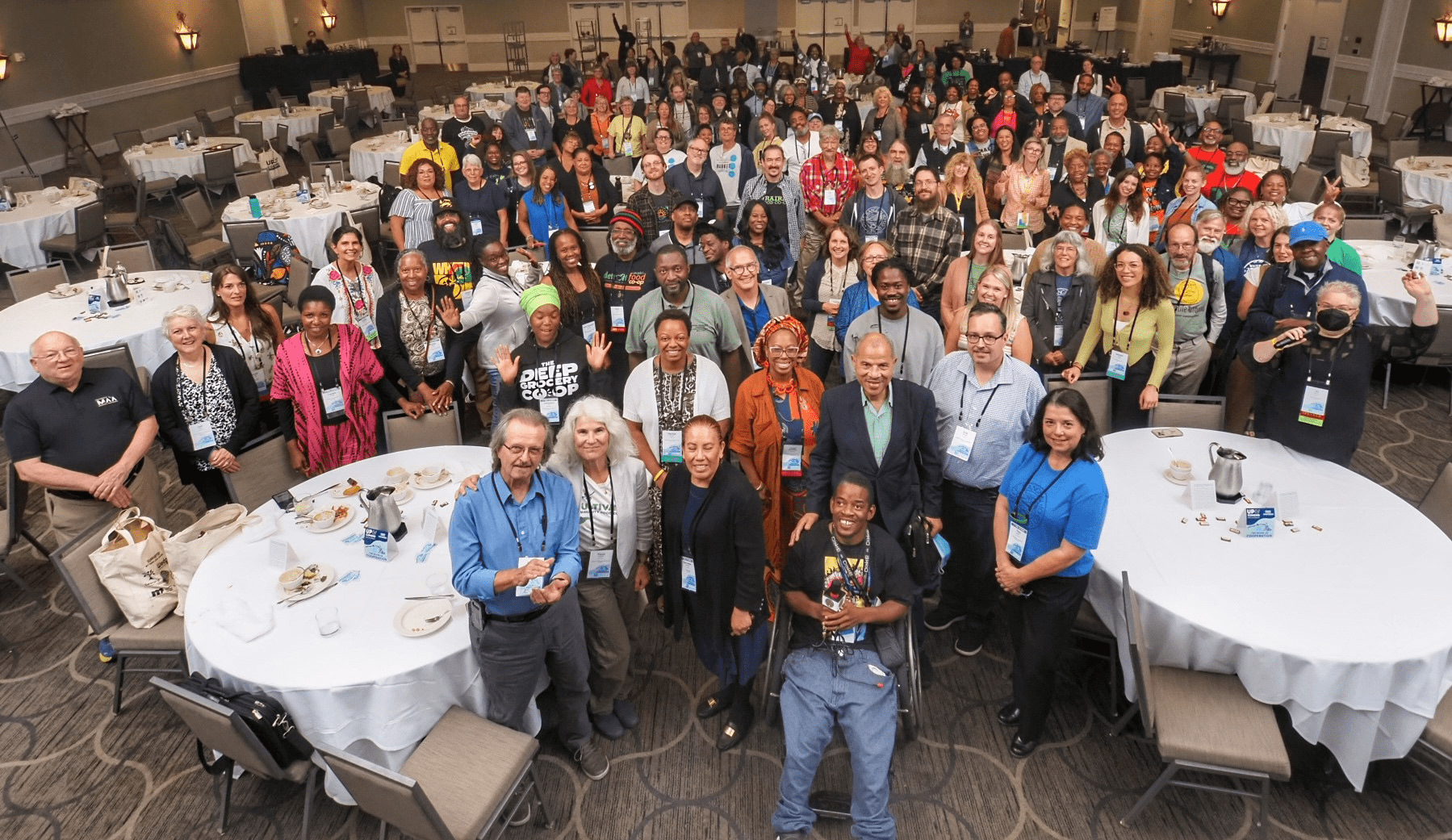

The discussion at the session took place in a larger context, one in which Black community organizers are playing an increasingly central role: about half of the 200-plus attendees at the food co-op conference this year were BIPOC. When the conference first convened in 2010, the audience and presenters were overwhelmingly White.

Moreover, in the world beyond the conference, many of the food co-ops slated to open in the next 12 months hail from BIPOC-led organizing efforts, building on the model established with Gem City Market in West Dayton, OH. For instance, Dorchester Food Co-op, after a decade-long effort in which Adams once served as project manager, just opened in Boston this month. Not far behind Boston are North Flint Food Market Co-op in Flint, MI; and Detroit People’s Food Co-op.

Medley cautioned, however, that many challenges remain. “In some communities,” she noted, “there are preexisting assumptions about what a co-op is. Food co-ops become symbols,” Medley added, which can “provoke fear and concern in some community members, particularly if they don’t see the food co-op as a space where they are welcome.”

Medley emphasized that organizing must be ongoing and cannot end when the business opens. Recent food co-op history shows the importance of this. A few years ago, organizers of the Renaissance Community Cooperative—a Black-owned food co-op in Greensboro, NC, that shuttered in 2019—named the failure to maintain movement energy as one key reason for the co-op’s demise, noting that “we failed to explore the strategic directions we needed to pursue to keep the movement growing.”

Food co-ops, Medley noted, are not just grocery stores but rather are part of a broader movement for a solidarity economy. “The thing that distinguishes co-ops is the association of people,” she emphasized.

“Cooperatives,” she added, “at least for Black folks, [are] about liberation.…Many of us are entering that space through food….That is not going to be the end. If you think you’re gentrifying,” she concluded, “open your vision beyond the grocery store.