A Black software designer knows that other local Black business owners have been turned down by local banks, so she doesn’t even bother applying for a loan. The owner of a home-based business hears that she can’t get a small business loan without using her home as collateral. A Muslim entrepreneur wouldn’t even consider applying for a small business loan because Sharia law prevents him from paying interest. A gay accountant is denied two consecutive business expansion loans and throws in the towel on trying again.

Stories like these have been far too common for far too long. But 2020’s double-whammy of the COVID pandemic and the racial justice reckoning that followed the police murder of George Floyd may have finally jolted awake civic leaders, nonprofits, philanthropists, and others to the jaw-dropping inequities in small business finance.

On January 20, 2021—Inauguration Day—Joe Biden issued Executive Order 13985, directing federal agencies to advance racial equity and support underserved communities through their programs. Three months later, the US Economic Development Administration (EDA) announced its new investment priorities. At the top of the list: economic development that advances equity through investments in underserved populations and communities in underserved geographies. The EDA’s Revolving Loan Fund (RLF) program has always supported economic development in distressed communities, and the executive order cemented its importance in helping revolving loan funds make loans to business owners unlikely to qualify for or seek out traditional capital.

It was in this context that the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, where I work, and our partners at Recast City reached out to EDA to help the staff and board members of 120 RLFs improve their track records in making small business loans to women, LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC entrepreneurs, groups that have historically been excluded from mainstream lending programs.

Divided into small groups, RLF staff and board members participated in online training and discussions for three months, digging deep to explore the differences between equitable lending and equal access to lending, then exploring program and policy changes to better reach historically excluded communities. It’s still early, with the first new loans made within this new framework still outstanding. But some significant changes are already emerging.

Mapping the Unequal Status Quo

By way of background, the effort to support BIPOC business began on a very unequal playing field. The extent of these inequities is staggering:

- Access to lenders: Last year, almost half (46 percent) of Black business owners said they had trouble getting capital. The same study found that both Black and Latinx business owners routinely lack lender relationships; with Latinx business owners, 39 percent said they had no lender relationship and 24 percent said they did not even know where to apply for capital. For Black business owners, the statistics are only marginally better, at 38 and 21 percent. A stunning 40 percent of Black business owners believe they will never have equal access to capital.

- Startup loans: While 11 percent of new business owners received startup loans in 2021, only eight percent of Latinx business owners and six percent of Black business owners received them. In 2021, the approval rate for private loans to White business owners was more than twice what it was for Latinx business owners. That same year, a third of all Black business owners and a quarter of all Latinx business owners took second jobs to help pay for their business expenses.

- Gender and LGBTQ disparities: There are other disparities in capital access. Only 25 percent of women business owners said they were likely to seek outside financing in 2019 versus 34 percent of men—and women are much more likely than men to finance their businesses with credit cards. Similar dynamics affect LGBTQ business owners, almost half (46 percent) of whom were turned down for all the financing they applied for in 2021 versus only 35 percent of non-LGBTQ business owners.

More broadly, White families have almost eight times the median net worth of Black families, and business equity represents 16.5 percent of assets for White families in the United States versus just 4.8 percent for Black families and 7.0 percent for Latinx families. Not surprisingly, building generational wealth is top of mind for Black and Latinx business owners, with 86 percent in a survey saying they are committed to this goal.

Nine percent of the new businesses launched in 2021 were started by Black entrepreneurs, three times more than in 2019.

In short, before 2020, the need for capital for small, historically excluded businesses was never greater. Then, COVID-19 hit. The pandemic shuttered hundreds of thousands of small businesses. Export restrictions severed supply lines for small manufacturers. Third-party restaurant delivery platforms’ fees eviscerated independent restaurants. Retail businesses that were considered “non-essential” had to close, but shoppers could still visit a big-box store (or dollar stores), which were deemed “essential” because they sold some grocery items. Of course, customers while there could also buy books, toys, cameras, and thousands of other non-essential products.

Not surprisingly, no small businesses suffered as much as those that were underserved, underbanked, and largely excluded from mainstream lending before 2020. During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, 41 percent of Black-owned businesses, 32 percent of Latinx-owned businesses, and 26 percent of Asian-owned businesses closed versus 17 percent of White-owned businesses. Monthly sales growth for women-owned businesses lagged three percentage points behind those owned by men.

Pandemic Lessons

Despite the enormous hurdles, entrepreneurs from historically disadvantaged communities are launching businesses at a brisk pace. Women started 49 percent of all new businesses in the United States in 2021, almost twice the percentage just two years earlier (28 percent). Nine percent of the new businesses launched in 2021 were started by Black entrepreneurs, three times more than in 2019. And over the past decade, the number of new businesses started by Latinx entrepreneurs grew by 44 percent versus just four percent for non-Latinx entrepreneurs.

The RLF program has, for almost half a century, quietly made grants to a network of over 500 revolving loan funds, which, in turn, loan money to small businesses and entrepreneurs. During the pandemic, the program—boosted through pandemic allocations within the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), accelerated getting capital to its network. Today, the combined capital base of EDA’s revolving loan fund portfolio nationwide exceeds $1 billion, according to some estimates.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

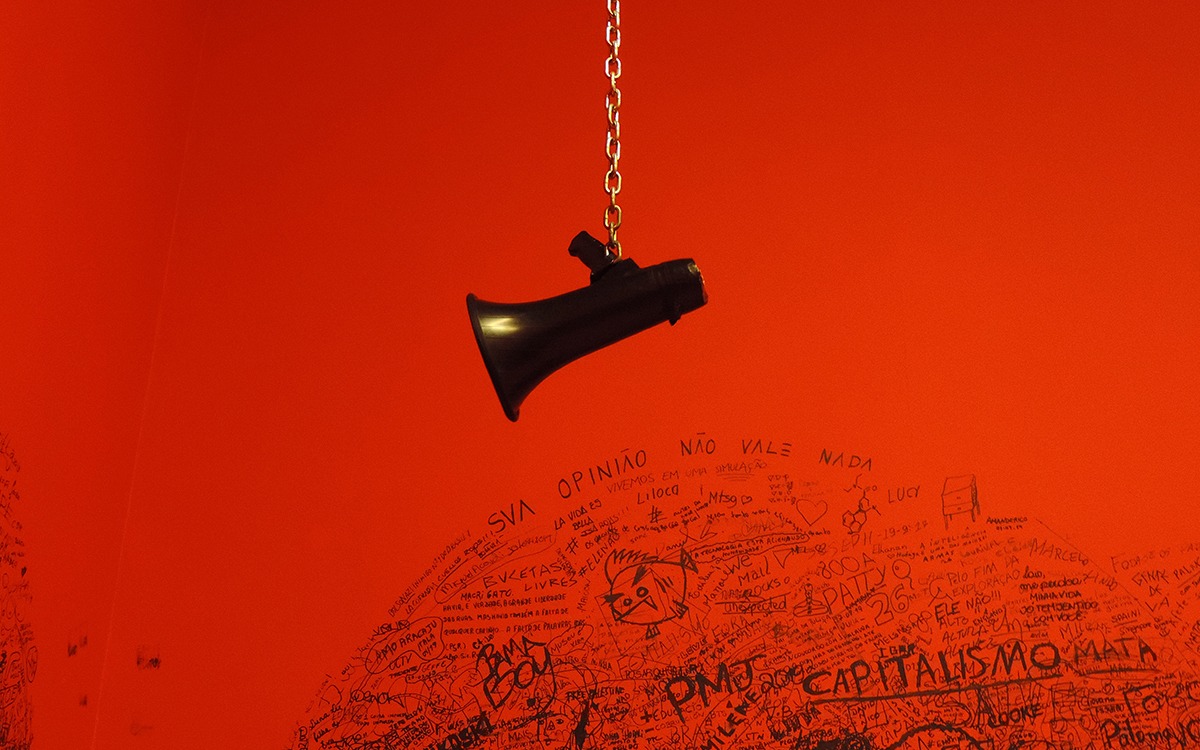

But simply lending money does not mean the money gets to historically disadvantaged businesses. The process is loaded with challenges, such as building trust with business owners, changing underwriting criteria, understanding cultural differences around finance, and mitigating risks.

Equitable lending is more than providing equal access. It requires addressing systemic inequalities and biases.

Recognizing that inequities in lending won’t solve themselves, EDA invited its RLFs to apply to participate in Equitable Lending Leaders, a 12-session online cohort training program designed and led by Recast City, in which participants were asked to devise strategies to improve their lending program design to more effectively reach historically disadvantaged businesses and thereby drive more equitable business outcomes in their communities. Over 12 sessions, representatives from more than 120 revolving loan funds came to these sessions to discuss hurdles, brainstorm ideas, share examples, and rework their lending strategies—providing a springboard for rethinking how to support historically excluded small businesses and change the status quo.

The 120-plus participating revolving loan funds ran the gamut from small to large, in every sense. Some focused on a single city or county, while others spanned multiple states. Some had just one or two staff, while others had dozens. Some were public entities, others were nonprofits. Some of them specialized in specific industries. But despite these differences, some common lessons emerged. Among them:

- Equal access to lending isn’t the same as equitable lending. Equitable lending is more than providing equal access. It requires addressing systemic inequalities and biases. One of the first things that Equitable Lending Leaders participants did was evaluate and fine-tune their definitions of “equity” and “equitable” to create a common vocabulary and shared understanding of this distinction within their own organizations.

- Don’t wait for business owners to come to you. There are scores of reasons why historically excluded business owners may be skittish about knocking on the door. These reasons vary from language barriers to decades of loan denials. And because revolving loan funds often receive loan referrals from their conventional banking partners, loan decisions often come with biases already baked in. It is vital to connect with people and groups who can build bridges and are trusted within the community the loan fund hopes to reach. “They aren’t the local banks and chamber of commerce,” one RLF director explained.

Equitable Lending Leaders participants have contacted faith-based organizations, set up tables at Pride festivals, and partnered with groups like National Black Farmers Association. The Apalachee Regional Planning Council in Tallahassee, FL, for example, participated in a Juneteenth event with 100 vendors of color. The Gulf Coast Economic Development District developed a Small Business Collaborative group to help broaden its outreach. Several RLFs have changed the metadata tags embedded in their websites to make their information easier for small business owners for whom English is a second language to find.

- Match funding with technical support. In addition to providing financial support, most RLFs also offer technical assistance, either on their own or in partnership with other organizations. This is particularly important for entrepreneurs from historically excluded communities. For example, in partnership with the Greater Augusta Black Chamber of Commerce, the city of Augusta, GA, provides a structured training program and one-on-one coaching for Black business owners in tandem with a grant and guaranteed loan program.

- Cut the red tape. Fear of red tape and of how the information provided in a loan application might be misused keeps some small business owners from borrowing the capital they need. As a result, many Equitable Lending Leaders participants have simplified their loan applications, only asking for the most essential information in writing and relying more on conversations with interested borrowers to round out the underwriting process. The Gulf Coast Economic Development District, for instance, simplified its loan application process after hearing from several business owners about problems that they had with the fund’s application. Some participants, like the Northeast Oregon Economic Development District, are adopting a pre-application to determine who might be ready for a loan now and who might need technical support first. Actions like these not only streamline underwriting but also build trust, which will pay future dividends.

If a revolving loan fund’s primary operating goal is…to support underserved small businesses, it may need to take bigger risks—or, more accurately, bigger perceived risks.

Many RLFs participating in Equitable Lending Leaders also found red tape in their own governance plan and other internal documents and are now exploring revisions. When asked to describe a breakthrough from the Equitable Lending Leaders program, one participant said, “I think it was the realization that our own RLF plan is what limits us the most in what we can do with our RLF funding.”

- Look for ways to buffer perceived risk. If a revolving loan fund’s primary operating goal is to preserve the fund’s capital, it will likely lean toward minimizing risk by making only what it considers to be the “safest” loans. But if its primary goal is to support underserved small businesses, it may need to take bigger risks—or, more accurately, bigger perceived risks. This might mean creating a loan guarantee fund, partnering with other entities to share risk, creating a specialized insurance product to insure against loan losses, or building a fee into each loan that goes into a pool to offset potential losses.

A Few Early Wins—And More Work Ahead

It remains too early to report comprehensive outcomes—the first round of new loans is happening now. But there are many promising signs. For instance, the Northwest Regional Planning Commission in Wisconsin has helped an LGBTQIA+ business owner to open a new boutique and coffee shop that beat its third-year revenue goal in just two months. It also helped a Latino business owner open a pastry shop featuring a family recipe that has been selling out its inventory every day and is now expanding its hours of operation to keep up with demand. The Region XII Council of Governments in Iowa helped the owner of a Chinese restaurant transfer the business to a new owner. The South Florida Regional Planning Council has helped a woman-owned cleaning service buy better equipment and grow its client base.

Getting capital to historically excluded small businesses is key to advancing racial equity. The pandemic shows us that federal funds can reach these businesses, but only if local and regional lenders organize effectively to do so.