(Illustration by iStock/VectorMine)

(Illustration by iStock/VectorMine)

Migration is often framed as a crisis: When the issue makes headlines, it’s portrayed as a burden, threat, or tragedy, and almost always politically intractable. In reality, migration represents an opportunity and a solution, and it needs to be disentangled from electoral politics. Indeed, we are at the beginning of a multi-decade, global trend of human movement, a trend which can be harnessed to unlock tremendous good for the world. And while the world’s attention is on the most visible symptoms of today’s broken systems, a small but scrappy group of actors is already working to build a better future for people on the move, the countries that welcome them, and the countries they (often temporarily) leave behind.

To understand why we need more and better migration, start with a basic fact: Never in history has there been such a strong link between global income inequality and demographic differentials. If you are in a country like Uganda, with a median age of 16, you are likely to be poor by global standards; if you are in a country like Germany with a median age of 45, you are likely to be rich. For decades, the best predictor of economic prospects is the country a person was born in, accounting for nearly two-thirds of global income inequality. But the gulf between rich and poor countries has also become a gulf between old and young: Even countries in Africa and South Asia with high economic growth rates are still not generating enough jobs to keep up with the youth entering the workforce. Labor Mobility Partnerships predicts that by 2050, 590 million of the 1.4 billion additional working-age people in low- and middle-income countries will have limited employment prospects, even as youth in these countries have an unprecedented awareness of the standard of living on the other side of the global tracks. Throw in the disproportionate effects of climate change on subsistence livelihoods and the fact that workers are paid 10 or 20 times their current wages for equivalent jobs in high-income countries, and little wonder that hundreds of millions across the Global South aspire to migrate to the Global North.

On the other side of the issue, broadly speaking, the Global North is characterized by low birth rates, unprecedented numbers of retirees, and looming, structural labor shortages that threaten economic and political stability. While immigration policies have prioritized high levels of education or family ties—and the political conversation tends to presume a basic scarcity of jobs—critical jobs in construction, agriculture, hospitality, and the care economy, including elderly care, cannot be automated. Even the transition to renewable energy is threatened by a shortage of some 7 million workers needed to do things like install solar panels on roofs. The workers who could solve these problems remain on their side of the global tracks.

Migration is not a problem in search of a solution; it is a solution waiting to be unlocked by thoughtful investment of resources and effort.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Migration for Impact

The immigration consensus of the past is already changing. Countries that are farther along the aging trend, such as Germany, Spain, Italy, and Japan, have begun to revise their visa policies to make it easier for workers to migrate, train, and work in critical trade and service industries. Even the US and UK have shown that immigration politics can be separated from workforce development, and seek to expand programs for well-managed migration to address labor needs in some key sectors. Meanwhile, countries on the “sending” side are positioning themselves to seek greater access to foreign labor markets. For example, at a 2023 press conference with German Chancellor Scholz, President Ruto of Kenya cited Germany’s need for 250,000 additional foreign workers and announced Kenya’s intention to pursue these job opportunities. This is part of a broader Kenyan “diaspora growth strategy,” which seeks the benefits of trade, investment, remittances, and knowledge gains that come through circular migration flows.

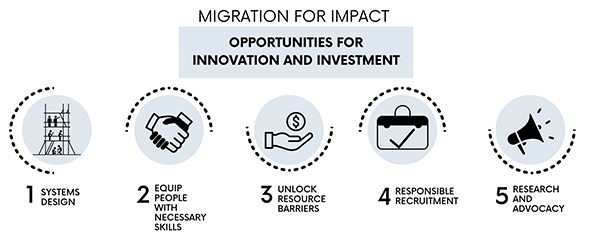

In parallel, social entrepreneurs are calling for a migration paradigm shift from crisis to opportunity and establishing a new field focused on facilitating access to livelihoods across borders. More legislative reforms are still needed, but policy shifts in the last five years or so mean that millions of work visas can already be utilized to transform the prospects of households and communities. And while a host of obstacles still remain between the rhetoric and the reality of facilitating cross-border livelihoods, these obstacles now represent tangible opportunities for innovation and investment to deliver impact for people on the move:

- Design scalable and high-quality migration ecosystems. When contemplating migration that can deliver massive income gains to low-income households and benefits to both sending and receiving economies—but must maintain public support in a difficult political climate—public, private, and civil society actors all play important roles in a complex system’s effective functioning. Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP) is an example of a systems designer that helps coordinate across employers, aspiring workers, recruiters, government agencies, and trainers to prioritize and direct the investments needed to establish “good labor mobility” in key corridors around the world. For example, LaMP works with elderly care employers to understand workforce needs, and has designed a program in partnership with the Spanish government to train workers in Colombia to meet these needs in both countries. LaMP has identified the role of each player in the system, applied for pilot funding, and plotted a path to transition the program to a sustainable long-term partnership. Well-designed systems, with accessible safe and legal pathways to employment, are also the only viable way to meaningfully reduce irregular migration given the underlying demographic and economic realities.

- Help aspiring migrants acquire skills and navigate opportunities. There are gaps in aspiring migrants’ knowledge of opportunities and how to navigate them, and they often struggle to overcome final hurdles such as language training or certifying their skills for the destination market. Social entrepreneurs from the South and North are tackling these problems through direct assistance to people who want to access livelihoods across borders. Imagine Foundation has helped thousands of young workers with technology skills from the Middle East and North Africa navigate the European job and visa application process. In Nepal, NSST is linking its local vocational training efforts to the German apprenticeship system. In India, Magic Billion is facilitating access to such apprenticeships in partnership with a local German-language trainer. Talent Beyond Boundaries works to extend labor mobility opportunities to refugees, working to match skilled refugee workers with employers in North America and Europe who need their talent.

Extending finance to unlock resource barriers. Finance is often a critical enabler for mobility. For example, Europe has hundreds of thousands of free or low-cost university slots for foreign students, but most students from low-income countries cannot save the year’s living expenses required for a student visa. To bridge that gap, Malengo now provides an income-share agreement and mentoring support that enables disadvantaged high school graduates from Africa to study and work in the EU. Its first cohorts come from households earning $1.40/day per capita, so even with part-time student jobs they have already increased incomes by 2,200 percent.

Language financing can also unlock opportunity. Learning a language requires a significant investment, but this investment must be made before a worker knows they have a job (or an employer knows they have a qualified worker). LaMP and partners like KOIS are developing financial products to solve this chicken-and-egg problem and expand language training in German, Japanese, and English.

More broadly, most of the models that are being developed to overcome barriers to mobility can eventually be sustained through private and public investment, eliminating the need for donor funding. That is, mobility creates so much value for workers, employers, and national economies that once a solution to unlock movement is developed and demonstrated, the business case for investing in the services needed to sustain it becomes obvious to non-philanthropic actors.

Build the responsible recruitment industry. The migration opportunity requires a good recruitment industry to provide the value-added services that enable workers and employers to find each other across borders. Building this industry includes developing and promoting business practices and tools that empower workers to make informed choices throughout their journeys. It also means influencing the development of markets so that value-added service providers are able to outcompete rent-seeking operations.

Traditionally, the recruitment industry has reflected the history of prohibitive OECD country visa policies, with many players operating in illicit or poorly regulated migration corridors. In response to abusive industry practices, responsible recruitment agencies like Staffhouse and Fair Employment Agency demonstrated that it is possible to shift market norms towards transparent operations and minimal up-front costs for workers, even in historically problematic geographies or sectors. By cutting fees to workers and providing better services, they were able to attract and identify higher quality candidates, for which employers are willing to pay a premium. Their experience will provide insights to the nascent industry preparing to serve better-regulated employment markets. Locally formed, responsible recruiter associations (such as efforts at various stages in the Philippines, Guatemala, and Kenya) can also help professionalize and consolidate the industry. Lastly, better monitoring tools can identify and root out rent-seeking behaviors. For example, LaMP’s WhatsApp-based worker survey has successfully gathered candid worker feedback on recruitment fees and working conditions; its low price point is attractive to employers, and LaMP anticipates reaching an unprecedented 40,000 workers in the US H-2A program this year.

- Gather and communicate the evidence of impact. Alongside these social entrepreneurs, researchers are studying migration for impact. For example, Michael Clemens concluded that removing barriers to human mobility would generate trillions of dollars of economic gains, and demonstrated that US employers with access to a seasonal work visa program also hired more workers domestically. Professors Mushfiq Mobarak and Johannes Haushofer have designed randomized control trials to empirically quantify income gains from migration, while Paolo Abarcar analyzed the impact of opportunity abroad on origin-country human capital formation, showing that the prospect of nursing jobs overseas dramatically increased the number of licensed nurses in the Philippines. To enable more evidence-based advocacy, Helen Dempster and the migration team at CGD has conducted action-oriented research to maximize the benefits of migration to destination and origin countries. Finally, Por Causa takes a systematic approach to shaping narratives about migrants in Europe, a critical input for future policy change and the sustainability of mobility efforts.

Funder Neglect

Nearly all of the actors in this emerging field face many more opportunities than they have resources to pursue, and few funders have the specific category of funding that matches their work. Donors may fund “livelihoods,” for example, but not cross-border livelihoods. They may fund “safe migration,” but not to the Global North. They may fund “climate,” but not the climate adaptation of migration. They may fund “justice” but rarely target laws that force willing employers to deny someone a job because of their nationality. They may fund “poverty reduction,” but that usually means 25 percent income gains in the country of residence, rather than 1,500 percent income gains in a high-income country.

My team at the Global Development Incubator (GDI) estimates that less than 0.5 percent of aid or internationally-focused philanthropy goes to any form of economic inclusion for people on the move, of which the vast majority is for economic integration of displaced people in low-income host countries. Domestic philanthropy supports migrants and asylum seekers already in high-income countries, but funding to enable people to safely and legally move across borders to opportunity is mostly unheard of, even though it is dramatically more cost-effective than supporting a migrant who has arrived through other channels.

Common Objections to Migration for Impact

Philanthropy and patient-capital investors could help this emerging field take flight, and generate social returns that dwarf those of global anti-poverty phenomena like microfinance or cash transfers. But there appear to be at least three common objections to supporting global mobility as an impact area, which can and should be overcome.

- The perception that legal migration is a niche issue. This underestimates how migration will shape the world in the coming decades, the scale of positive impact if we harness it, and the disproportionate costs of waiting until people are already on boats or desert caravans. 900 million people say they would move across borders if they could, and many more want to do so temporarily, including half of adults in Sub-Saharan Africa. Perhaps talk is cheap, but nearly 300 million are on the move already, even with historically limited access. And neither the $50 billion spent annually on militarized border control nor the trillions of dollars in income gains at stake are niche numbers.

- Concerns about “brain drain.” With few exceptions, the specter of depriving a worker’s birth country of critical talent is consistently disproven by empirical evidence, primarily because investment in human capital responds to economic opportunity. An opportunity to work abroad encourages more people in a given country to obtain the skills for that opportunity than can go abroad. Moreover, “brain drain” requires the tendentious assumptions, first, that the Global South has a limited stock of talent (when in fact the shortage is one of opportunity) and, second, that migration will be permanent (when twice as many people would prefer temporary to permanent migration). Moreover, the emerging field supporting cross-border livelihoods is not mainly focused on migration opportunities for doctors or scientists, because these are already accessible (though the US lags behind), and even here, the long-term effects of such movement are generally positive through “brain circulation” and other effects. Rather, the hundreds of millions of workers needed in the Global North over the next three decades will generally not require advanced degrees, which is good news for the hundreds of millions in the Global South seeking work without such degrees.

- Many funders consider the issue politically intractable. Donors in the US, where the issue of immigration reform has been stalled for decades, may assume that funding migration for opportunity means making long-term, uncertain bets on legislative change. However, there is scope to immediately begin transforming lives without any further policy change. Canada and countries in Europe, East Asia, and Oceania with governments from left, right, and center have all recently expanded visa pathways to address workforce shortages in key industries. And even the US has untapped opportunities for impact in agriculture, some high-skilled visa programs, and health care. As noted earlier, under current policies there are millions of vacancies in high-income countries that could be filled legally by workers from the Global South, with the necessary resources and problem-solving.

Opportunity to Innovate and Scale Transformative Migration Efforts

The scale of potential impact and the window of opportunity that has opened is a compelling reason for problem solvers, funders, and investors to shift effort and resources into migration for impact. Because income differentials are so high across borders and interventions can eventually be sustained by the private sector, a cross-border livelihood initiative may achieve a 300:1 ratio of income gains to the philanthropic dollar. But getting returns like these requires innovative solutions to complex obstacles, donors willing to make early bets on an idea or an organization, and patient capital to get to scale. There are a variety of roles to play:

Social innovators with expertise in human-centered design, catalyzing systems change, and innovative finance should look for opportunities to deploy these skills to design client-centered mobility solutions for aspiring migrants. Organizations working on topics like youth employment and livelihoods in LMICs or anti-trafficking are well-positioned to contribute to migration for opportunities. Instead of only trying to deter risky migration, or when skilling efforts result in minimal job placements, actors working with youth should explore how to link them to employer demand in high-income countries through safe and legal channels. These efforts should attract increased attention from researchers to fill the gap in evidence on the impact of mobility on migrants and their communities, which will ultimately strengthen the case for allocating greater resources to migration for opportunity.

Philanthropists should elevate migration for opportunity (or “cross-border livelihoods”) to a priority funding area, which will complement investments in climate-change, youth employment, and women’s economic empowerment. It takes a long time between identifying an opportunity to deliver transformative income gains and actually moving individuals into prosperity at scale. In between comes complex systems analysis, stakeholder coordination, solution design, testing, and piloting. And then, individuals may require multiple years to learn a language or complete an apprenticeship. Few funders today target opportunity migration, though projects in their final stages might tap adjacent pools of funding earmarked for skilling or for a particular geography. However, it is much harder to fill the critical gap in early-stage funding for innovation and design of solutions, and almost impossible to find partners with the foresight, patience, and resources to fund mobility from idea to scale. Western Union Foundation and Schmidt Futures are two first movers, but the field needs many more providers of early-stage flexible grants, or else unrestricted funding, to help identify, design, and test solutions that could unlock big migration opportunities.

Government and multilateral donors should adopt labor mobility as a critical strategy to combat global poverty and inequality, as well as human trafficking. A few bilateral funders—including DFAT, USAID, and GIZ—are testing labor mobility as an intervention in specific nationally relevant corridors. The World Bank has recently announced plans to launch Global Skills Partnerships, which train workers for both “home” and “away” tracks. But the opportunity—both the number of people who could be impacted and the potential income gains (it only takes 10M workers for $1 trillion in gains)—vastly exceeds the current resources and attention allocated. Bilateral and multilateral funders should expand their vision and develop new frameworks for using aid to catalyze high-impact South-North migration. They can provide innovation grants through platforms like DIV and FID; larger grants for pilot programs that place workers in jobs across borders, helping to meet livelihood and employment objectives; and credit guarantees to launch new finance solutions. As implied earlier, aid funding for labor mobility can eventually be replaced by public-sector subsidies or private investment.

Impact-linked investors should deploy capital to help stand up a good mobility industry. Enabling access to opportunity across borders unlocks tremendous economic value, which benefits the private sector in addition to individual workers. Because of this, most mobility interventions can be sustained in the long term through commercial capital, including finance for migration-related service providers and for individual upskilling and education. But patient capital and impact-linked investment must play a critical role in the interim because of the time horizons involved, the limited track records of current solutions and finance products, and the importance of shaping the mobility industry in a way that ensures responsible business practices. Creators of new finance solutions are presently seeking credit guarantees and program-related investment to enable more risk-sensitive investors to participate. There are also emerging opportunities for development finance institutions and impact investors to make equity and debt investments in mobility solutions.

Grabbing the Future Now

Because it takes time to deliver scaled impact through migration, the social impact community must multiply its efforts now, before windows of policy opportunity shift or populations lose faith in the ability of these new pathways to deliver the promised benefits of bolstering workforces or regularizing movement. Without action today, we risk returning to a vicious cycle where unmanaged migration feeds public opposition to legal migration, which in turn feeds more irregular migration.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Jason Wendle.