We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

Dr. James explains the power of giving: why leading with a gift always wins

Lead with a gift: The primal-giving game

Biologists model sustainable giving in nature with a game.[1] This primal-giving game models reciprocal altruism.[2]

What’s the best strategy in this game? To answer this question one professor held an international computer gaming tournament. With many rounds and many players, strategies got complicated. How complicated? He explains,

“An example is one which on each move models the behavior of the other player as a Markov process, and then uses Bayesian inference to select what seems the best choice for the long run.”[3]

So, what worked? When – as in nature – winners replicate and losers don’t, this complexity disappeared. One strategy always won. Lead with a gift, then act reciprocally.[4]

This result attracted a lot of attention. So, another, much larger tournament was held. The winner? Same answer. Every alternative – no matter how complex – eventually lost to this simple strategy.

Another version of the game added a twist. It allowed for miscommunication. Sometimes sharing was reported as not sharing. In this version, a new winning strategy emerged. Lead with two gifts, then act reciprocally.[5] To play the game yourself, go to https://ncase.me/trust/

Lead with a gift: Back to relationships

So, how does game theory apply to real-world fundraising? Start with this:

- Go see donors.

- Bring a gift.

When bringing a gift, make sure it’s a good one. What does that mean? A good gift signals a “helpful reciprocity” relationship. These relationships are personal. They encourage generosity. Transactional relationships are different. They aren’t personal. They don’t include generosity.

A good gift says several things:

- This is not transactional.

- This is personal.

- I care enough to know what you like.

- I want to make you happy.

Not all gifts are good. Cash rarely works. It’s transactional, not personal. In experiments, cash benefits can actually reduce giving.[6]

A “gift” given as an explicit trade is not a gift. It’s a transaction. In experiments, these strictly contingent “gifts” can also reduce giving.[7]

A financially costly gift can be risky. It can send financial or transactional signals. It can trigger unwanted feelings of financial obligation. For charities, it can also feel wasteful.

But a gift can be valuable without feeling costly. This is because in a social context, “cost” means extra cost. Consider the same gift with different “extra” cost.

- Social gift: “I own a condo on Padre Island. It’s empty during spring break. You can use it as my gift to you.”

- Awkward gift: “I went on Airbnb and rented a condo for you on Padre Island during spring break. You can use it as my gift to you.”

The gift value is identical. But in one case, it feels uncomfortable. In the other, it doesn’t. The difference is the extra cost.

Lead with a gift: A simple fundraising example

Games and theory are fine. But let’s get practical. What actually works in fundraising? When I first became a college president, I wanted to know the answer. I started by looking at schools with our same religious affiliation. Usually age, endowment, alumni, and tuition predict contributions.[8] And this was true for our schools, too. Except for one.

One small school was raising money out of all proportion to its size. It had only one or two frontline fundraisers. Although located in rural Tennessee, it received major gifts from across the country. I had to find out why. So, I went there to see what was going on.

The long-time fundraiser explained his unique approach. He had a disabling condition. Sometimes, he had “bad days” when he couldn’t work. There was no way to predict when this would strike. So, he couldn’t do the one thing that all other fundraisers do. He couldn’t reliably keep appointments.

Here was his solution. He would fly to a location with a list of donors in the area. He would drive to the first house. He would knock on the door. If the donor was home, he would hold out his card, introduce himself and say,

“Since I was in the area visiting other friends of the school, the president asked if I would drop off this small gift to thank you for your years of support.”

If the donor was busy, this took no more than a minute of their day. But here’s the reality: He was always invited in.

During the visit, he learned about the donor’s history with the school. He updated them on the latest happenings. Because this was a religious school, he would ask about their lives and ask to pray with them. The meeting ended by leaving behind a request “from the president” to consider a specific gift. But this always came with an explanation that no decision should be made on that day.

These little meetings became more powerful because he returned every year. He knew their lives, their families, their connections, and their charitable passions. If the donor wasn’t home, he would simply leave the gift with a personal, handwritten note.

He explained to me,

“I see more donors than any five fundraisers I know. The reason is simple. No dead time. If a meeting runs long or short or the donor isn’t home, it doesn’t matter. As soon as it’s done, I drive to the next home.”

Harold Seymour recounts another “old school” example of door knocking. American Cancer Society canvassers began,

“Good afternoon! I have here your copy of Cancer’s ‘Seven Danger Signals.’ May I come in?”[9]

The point isn’t that these are universal solutions for fundraising.[10] The point is that these achieved,

- Go see donors.

- Bring a gift.

And they worked.

Game theory: Able and willing to reciprocate

This strategy matches the game. First, consider the previous article on capacity for reciprocity.[11] Do personal visits change the “predicted frequency of future meetings?” Yes.

Mentioning other friends of the school in the area fits, too. How can a charity in rural Tennessee become a “neighbor” to a donor in California? It visits. It visits every year. It reminds donors that other community members are nearby as well.

Next, consider reciprocity signals. The visit leads with a gift. The gift is delivered personally. It’s presented as not financially costly. (“I was already in the area visiting others.”)

The visit emphasizes personal connections. It includes appreciative inquiry and listening. Every piece signals a personal, social relationship. Although a gift request is left behind, the response is purposely postponed. This prevents any transactional ending to the visit. It keeps things social.

Lead with a gift: A big fundraising example

So, that’s cute. But maybe what works for a tiny little religious school doesn’t apply to you? OK. How about a big prestigious university? NYU went from near bankruptcy, raising only about $20 million per year, to completing the nation’s first billion-dollar campaign. Naomi Levine explains how it happened in her book.[12]

In it, she describes her process of working with a prospect. The purpose of the first meeting, usually a breakfast, was to ask for their advice on some university policy. The conversation would uncover their connections or interest with different university programs. The goal was to schedule a campus visit.

At this campus visit, the prospect would

- Take a tour

- Have lunch with the president, and

- Visit with faculty in areas of interest.

The next goal was to then involve them in some aspect of the university. Levine explains, “If there was going to be a concert or film festival at the Tisch School of the Arts, we would invite them to that. If there was a seminar at the Law School, we would invite them to that. If we had an advisory committee on filmmaking, we would, if appropriate, invite them to sit on that committee.”

This all took place well before any donation request. She explains, “The quicker you ask, the less money you will receive.”

Game theory: Willing to reciprocate

Consider how this series of experiences builds the right relationship.

- The charity signals that the donor is valued. (We need your advice.)

- It leads with social gifts. (Have lunch at our place. Take a tour. Meet the president.)

- It follows with a personally meaningful experience. (The lecture, concert, or advisory committee is carefully selected to match their interests.) This gift shows, “We care enough to know what you like.”

This process repeatedly signals a helpful reciprocity social relationship.

- The prospect gives socially. (He gives advice and participates.)

- He receives socially. (He receives honor, events, meals, and experiences.)

- This sharing exchange is always non-transactional.

- The gifts are not presented as financially costly. (The extra cost of inviting this person to an event is minimal.[13])

- The process is far removed from any financial donation request.

Game theory: Able to reciprocate

Giving in the primal game has an unbreakable law:

Giving must be seen by partners who are able and willing to reciprocate.

The previous social signals help build relationship. They suggest a willingness to reciprocate. What about the ability to reciprocate? The tour and experiences help here as well. They display the university’s attractive features.

But reciprocity goes further. It can come not only from the nonprofit, but also from a supporting community. How does this work? At these meetings with prospects, the fundraiser rarely went alone. Levine explains,

“if a person was in real estate, we would discuss what real estate person should meet with him. If he was in insurance or finance, we would think of people who we felt were his peers and someone that he would respect. During the twenty years that Larry Tisch [billionaire owner of CBS television] was chairman, he joined most of those meetings.”

Notice how the process created a supportive audience with enormous capacity. This wasn’t just the wealthy charity itself – displayed during the tour. It was also important professional “neighbors.” It was even a recognized billionaire. All of these pieces work together to signal ability and willingness for reciprocity.

What’s the point?

These stories show practical examples of strategies that worked. Some worked for small charities. Others worked for large ones.

The point isn’t that any approach is the universal solution for fundraising. The point is that the primal game matches reality. Sending signals that giving will “be seen by partners who are able and willing to reciprocate” works. Leading with a gift is a great signal of reciprocity. And it works.

Special events: A practical application of the game

Understanding the primal-giving game provides guidance. It can help answer practical questions. Let’s look at a contentious one: Are special events a good idea in fundraising?

Some people love them. Some people loathe them. So, who’s right? The first problem is definitions. There are two types of “fundraising” events. An event can “lead with a gift.” Or it can “lead with a transaction.”

Special events: Leading with a gift

A personal invitation to an attractive event can be effective – if it’s a gift. It can signal a social, “helpful reciprocity” relationship – if it’s a gift. It can connect a donor with meaningful parts of the charity. It can provide recognition, honor, and gratitude after a donation. It can build a donor community that supports future donations. It can do these things – if it’s a gift.

These events aren’t transactional. They are a gift to attendees. (The cost is paid by the charity or a donor.) Because they aren’t profitable, these events can’t be the end goal. And that’s a good thing. This shows that the important work is not just the event. The important work is the whole fundraising process.

Special events: Leading with a transaction

Transactional events are different. They charge fees, provide a service, and generate revenue. They can make a profit. The profit can help the charity.

Transactional events are easy to sell. The event timing creates a deadline. This helps motivate sales requests. People with no idea how to fundraise can sell event tickets or table sponsorships. These are just consumer products with a charitable hue.

Administrators like these events. They provide an immediate quid-pro-quo return. And that’s the problem. Even when these “work,” they work only transactionally. Just a bit more income than cost is a “success.” One group of data analysis researchers noted,

“Special events are generally accepted to be the least cost-effective way for nonprofits to raise revenue.”[14]

Compared to actual fundraising, special event sales are inefficient. Some accounting professors have even found charities that hide these inefficient numbers.[15] Charities move these barely profitable events into separate entities. This protects the charity’s own efficiency ratings.

Transactional events vs. social relationships

But don’t such events lead to great relationships and later donations? Not really. Instead, they signal a completed, transactional relationship.[16] Think about it. Suppose a new work colleague says to you,

“The wife and I are hosting a big New Year’s Eve party. We’ll have great food and drinks and even a local band! We would love to have you come.”

How do you feel? What does this signal about your relationship? Then he adds,

“Tickets are $75. You can buy in advance or pay at the door.”

Now, how do you feel? How does this change the signal about your relationship?

Research supports this feeling about transactional events. One study used in-depth qualitative interviews. It examined a “successful and well-run” money-making charity event. It found that the event,

“Had little effect on participant’s relationship with the charity.”[17]

Another study looked at over 10,000 nonprofit tax returns. It found that increasing revenue from special events had almost no impact on later donations.[18] In fact, increasing operations revenue (people paying for the nonprofit’s services) actually worked better. This created more than twice as much donations growth as increasing special events revenue did.

These transactional events don’t help fundraising. There’s another problem. They have a hidden cost. They can strain staff resources. Worse, they can be an attractive distraction for fundraisers.

Event work is urgent. (People are coming!) And it’s relatively easy. (Don’t believe me? Advertise for an entry-level “event coordinator” and also for an entry-level “fundraiser” with identical pay. Compare the response.) But urgent and easy doesn’t mean it’s important. It doesn’t mean it helps with real fundraising.

And the answer is … it depends

This mixed reality of special events matches theory and research. It also matches the wisdom of experience. As Naomi Levine explains, her feelings could be negative:

“Most special events, especially dinners and galas, were not cost effective …. In addition, the details of any dinner or gala are tremendous and also require a great deal of staff time.”[19]

Or they could be neutral:

“[If] the event is used as a way of soliciting gifts prior to the dinner, or if the dinner is sponsored by an organization or person, then it might be viewed as worth the amount of time, effort, and costs involved.”[20]

Or they could be very positive. This happened with an award dinner recognizing top donors because,

“Donors enjoy such rewards and deserve it.”[21]

These mixed feelings match the game. “Sold” events signal a transactional relationship. They produce, at best, small, transactional wins. “Gifted” events signal a personal, helpful relationship. They can deliver recognition and gratitude. This can produce transformational wins.

Conclusion

Leading with a transaction can be a way to earn an immediate profit. But it’s not a good way to encourage generosity. Leading with a gift won’t earn an immediate profit. But it is a great way to encourage generosity.

This winning first step is the same in the game and in the real world. Leading with a gift works.[22] In both the primal-giving game and in modern fundraising, the answer is the same:

- Go see donors.

- Bring a gift!

Footnotes:

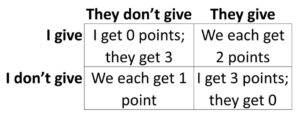

[1] This is known as the iterated prisoner’s dilemma game. For example, two players both face these payoffs:

where each must choose before knowing what the other will do.

[2] Boyd, R. (1988). Is the repeated prisoner’s dilemma a good model of reciprocal altruism? Ethology and Sociobiology, 9(2-4), 211-222.

[3] Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, W. D. (1981). The evolution of cooperation. Science, 211(4489), 1390-1396. p. 1393.

[4] Id.

[5] This “generous tit-for-tat” offsets the problem of accidents or miscommunications that might otherwise create a negative reciprocity tailspin. Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (1992). Tit for tat in heterogeneous populations. Nature, 355(6357), 250-253.

[6] For an example where cash payments reduce charitable behavior, see Ariely, D., Bracha, A., & Meier, S. (2009). Doing good or doing well? Image motivation and monetary incentives in behaving prosocially. American Economic Review, 99(1), 544-55. For an example where the promise of cash payments reduce guilt and increase satisfaction for those who don’t support the charity see Giebelhausen, M., Chun, H. H., Cronin Jr, J. J., & Hult, G. T. M. (2016). Adjusting the warm-glow thermostat: How incentivizing participation in voluntary green programs moderates their impact on service satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 80(4), 56-71.

[7] Newman, G. E., & Cain, D. M. (2014). Tainted altruism: When doing some good is evaluated as worse than doing no good at all. Psychological Science, 25(3), 648-655; Zlatev, J. J., & Miller, D. T. (2016). Selfishly benevolent or benevolently selfish: When self-interest undermines versus promotes prosocial behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 137, 112-122.

[8] See, e.g., Terry, N., & Macy, A. (2007). Determinants of alumni giving rates. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 8(3), 3-17.

[9] Seymour, H. (1999). Designs for fund-raising (2nd ed.). The Gale Group. p. 77.

[10] He shared a story how one school with a similar religious affiliation in Malibu, California explained that such a strategy wouldn’t work with their high-net-worth donors. He said, “I didn’t want to argue, but I looked at their list of top donors, and a third of them were people I had been visiting this way for years.”

[11] See Chapter 3. Primal fundraising and capacity for reciprocity: I’m with them because they’re important to me!

[12] Levine, N. B. (2019). From bankruptcy to billions: Fundraising the Naomi Levine way. Independently published.

[13] Note that leading with a gift is still costly. The lunches, tours, meetings, and events cost money. Even when the “extra” cost is small, the total cost is still substantial. So, just like in the game, if the prospect never gives back financially the charity definitely loses.

[14] Krawczyk, K., Wooddell, M., & Dias, A. (2017). Charitable giving in arts and culture nonprofits: The impact of organizational characteristics. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(4), 817-836. p. 828. table 2.

[15] Neely, D. G., & Tinkelman, D. P. (2013). A case study in the net reporting of special event revenues and costs. Journal of Governmental & Nonprofit Accounting, 3(1), 1-19.

[16] This also risks blunting the donation impulse by providing a marginally-beneficial, transactional option that apparently fulfills the reciprocity obligation.

[17] Woolf, J., Heere, B., & Walker, M. (2013). Do charity sport events function as “brandfests” in the development of brand community? Journal of Sport Management, 27(2), 95-107. pp. 95 & 104.

[18] Krawczyk, K., Wooddell, M., & Dias, A. (2017). Charitable giving in arts and culture nonprofits: The impact of organizational characteristics. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(4), 817-836. p. 828. Table 2.

[19] Levine, N. B. (2019). From bankruptcy to billions: Fundraising the Naomi Levine way. Independently published. p. 53.

[20] Id. p. 53.

[21] Id. p. 41.

[22] The strategy of “leading with a gift” is by no means limited to fundraising. A crass application is covered in the movie Tin Men about siding salesmen in the 1960s. The great salesman, Bill Babowsky, explains,

“You want to get in good with people … you want to win their confidence? Good thing to try … get a five dollar bill, take it out when the guy’s not looking, drop it on the ground. Ask the guy if he dropped his bill … Right away this guy is thinking you must be one hell of a nice guy … you’re in. You’ve got him for whatever you want now.”

Levinson, B. (1986). Tin men. [Movie script]. p. 41. http://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/Tin_Men.pdf

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- How transactional donor relationships kill generosity

- Finally, the questions you should ask that have been proven to lead to gifts from wealth

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

If your relationship with donors is merely transactional, you’re losing money

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!