We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

Dr. James explains how to harness friendship reciprocity to unlock heroic donations

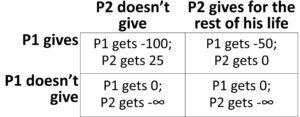

Biologists model sustainable giving in nature with a simple game.[1] The heroic donation comes from an extreme version of this game.

The numbers game

In the extreme version, two players each risk becoming either Player 1 or 2. The payoffs are these:

Each player faces the chance either to save (Player 1) or be saved (Player 2). But saving the other player means taking an unrecoverable loss. If players choose rationally, Player 1 won’t give. Player 2 will die. One of the players will be Player 2. So, one of them will die.

There is an alternative. Both players could agree to a “mutual insurance” pact. This is called friendship reciprocity.[2] Both agree to deliver transactionally unjustified aid in a time of crisis. Both players would survive.

But there is a problem. At the time of need, there is no way to enforce the agreement. At the point of crisis, giving is irrational. It’s a losing move. Thus, picking the right friend is both critical and difficult.

The simple game has an unbreakable law:

Giving must be seen by partners who are able and willing to reciprocate.

In the extreme game, the law still applies. But now, potential partners are those who are able and willing to save in a crisis. They are willing to do so even when it’s sacrificial. Simple reciprocity no longer works. Only friendship reciprocity can help.

The natural game

The game models the natural world. In the natural world, friendship reciprocity relationships are critical to survival.[3] But they are tricky.

The dilemma is this:

- Having a reliable friend is valuable. Having a fair-weather friend is not.

- Being a reliable friend is expensive. Being a fair-weather friend is not.

Picking a “fair-weather” friend means when the crisis comes, you die. Picking a loyal – but powerless – friend has the same result. Being a “fair-weather” friend isn’t costly. But actually saving a friend means taking a permanent loss.

This dilemma leads to strategies. It leads to natural rules for picking mutual insurance partners. Professors Tooby and Cosmides originated the evolutionary theory of friendship reciprocity.[4] They write that the evolutionarily optimal selection of friends depends on the following:

- “Number of friendship slots already filled.”

- “Who emits positive externalities?”

- “Who is good at reading your mind?”

- “Who considers you irreplaceable?”

- “Who wants the same things you want?”[5]

These factors reflect a close, mutually beneficial relationship. They show who is valuable to you. They show who is invested in you. They show who is with you.

These factors also reflect emotional bonding. This bonding distinguishes a fair-weather friend from a reliable friend. At the moment of crisis,

- A fair-weather friend acts rationally.

- A reliable friend acts emotionally.

The fundraising game

A charity can structure giving opportunities to allow heroic displays.[6] A donor can be seen to sacrificially protect his people or values. He can even do it in an extreme setting. This can signal reliability as a friendship insurance partner.

A charity can do more. It can build a community of powerful friends. This creates an ideal audience for a heroic display.

Even more, a charity can act as a reliable friend. It can become an ideal audience for a heroic display. But how? How can a charity become an attractive friend?

The answer starts with the evolutionarily optimal factors. These can also apply to the charity. Does the charity,

- Fit with the donor’s other charity relationships? [“Number of friendship slots already filled”]

- Provide access to valuable relationships or benefits? [“Emits positive externalities”]

- Understand the donor’s values and preferences? [“Good at reading your mind”]

- Value the donor personally? [“Considers you irreplaceable?”]

- Share the donor’s goals and values? [“Wants the same things you want?”][7]

Answer “no” to any of these questions, and a major gift is unlikely. Of course, these evolutionary theorists weren’t writing about major gifts fundraising. But the rules of the game still apply.

A simple example

One fundraiser for a law school shared this story.

“I heard that one of our donors was in the hospital. So, I stopped by just to visit. He joked about me hoping to collect on the estate gift. But you know, ever since that meeting, our relationship completely changed. He has been much more strongly connected to the school. That little visit made a huge impact.”[8]

Can visiting a donor in the hospital work? Theory says, yes.[9] Showing support during a time of need signals friendship insurance reliability.

In a primitive context, this timing is key. It is precisely when fair-weather friends will vanish. Anthropologists explain,

“Individuals who are sensitive to current probability payoffs have incentive to renege on exchange commitments to a disabled exchange partner when they are most in need … prolonged injury or illness renders an individual incapable of reciprocating at a time when he or she is most in need of investment.”[10]

Showing solidarity is nice. But showing solidarity during a time of need is more meaningful. It helps separate true friends from fair-weather friends.

A simple answer

Signals of helpful, social-emotional relationships encourage generosity. Signals of transactional relationships don’t. We can see this in game theory. We can also see it in evolutionary theory.

But a fundraiser can get the same answers without math or biology. Just ask, “What would a good friend do?”

This simple question is powerful.

Q: Should I actually visit donors?

A: What would a good friend do?

Q: Should I call?

A: What would a good friend do?

Q: Should I write a personal note?

A: What would a good friend do?

Q: It’s so cheap to just spam the donor’s inbox. Should I do that?

A: What would a good friend do?

What are successful major gifts fundraisers like? Theory predicts it. Research confirms it. They tend to excel at friendship-related skills.

Dr. Beth Breeze studied personal skills in fundraising.[11] Her three-year research project found the most important factors. These included,

- “High emotional intelligence”

- “An ability to read people”

- “A great memory for faces, names, and personal details”

- “A tendency to engage with people” even outside their job, and

- “A love of reading” particularly “popular psychology books.”

Experience confirms this, too. Naomi Levine led America’s first billion-dollar fundraising campaign. She describes the successful fundraisers behind it. They,

“Had to be ‘interesting well-read people’ so that donors would enjoy talking and relating to them, for fundraising is not primarily about ‘asking people for money’ … It is the cultivation of people. It is developing relationships.”[12]

Time and behavior

Building charity friendship alliances takes time. CASE suggests donor cultivation of 2 or 3 years before making a major gift request.[13] If this were just a transaction, such a time commitment would make no sense. No one needs 3 years to gather transactional data. But these major gifts are not simple economic transactions. Again, Levine explains,

“When you sit down with someone and try to develop a relationship, you can’t just say, Oh, Mrs. Jones, would you give me $100 million? That’s not the way it works. It’s a slow process. The quicker you ask, the less you get. Developing relationships and trust often takes a long time.”[14]

Of course, developing such relationships is not just a matter of waiting for time to pass. The charity must actually behave as a friend. It must signal that it is able and willing to act as a reliable friend.

At the moment of crisis, cheating is the rational choice. Friendship reciprocity is a bet. It is a bet that a friend will behave non-rationally. Signaling a close, personal, emotional relationship builds friendship alliances. Signaling a dispassionate, formal, detached relationship kills them.

The heroic donation audience

The crucial relationship can be with the charity. But it can also be with other supporters. They can be potentially valuable friends. They can be the key audience for the heroic gift. Levine explains,

“Fundraisers can’t go out on their own and raise the money. Who did I know? Did I know all the affluent people in New York City? Obviously not. The board gave me names. They made suggestions … They were not going to give to me; obviously, they were going to give to people with whom they had a relationship. Peers are important. A board gives you such relationships.”[15]

High-capacity fellow donors make an ideal audience for heroic donation displays. Such an audience encourages transformational gifts.

The “one big thing”

The one big thing in fundraising is still the same: Advance the donor’s hero story. The natural origins of heroism, and the heroic donation, come from friendship reciprocity.

The heroic donation displays friendship insurance reliability. But this display is pointless without the right audience. It requires an audience of potentially valuable friends. It requires an audience with the ability and willingness to save in a crisis.

The charity can build this audience of reliable partners. It can also act as a reliable partner. This creates an environment that supports the heroic donation. This helps to advance the donor’s hero story.

Postscript: What about friends with benefits?

A hero is a sacrificial protector. A heroic gift demonstrates sacrificial protection. This signals attractiveness as a mutual insurance partner. Does this “attractiveness” extend to romantic partnerships?

In one experiment, women rated the attractiveness of different men. But they didn’t get pictures. Instead, they got only behavioral descriptions of the men.[16] The result? Women generally preferred altruists for friendships and long-term relationships. But that wasn’t enough.

They reserved the highest attractiveness ratings for men showing heroic altruism. The ideal combination was “dependably brave and altruistic.”[17] Consider this in terms of mutual insurance. Such men,

- Could be predicted (“dependably”)

- To deliver transactionally unjustified aid (“altruistic”)

- In a crisis (“brave”).

In the 80’s, Bonnie Taylor sang, “I need a hero.”[18] Apparently, others share her feelings!

Men also seem to respond to this. In one experiment, heterosexual men donated twice as much to charity when observed by a woman rather than by a man.[19]

Still, the best display is not just altruism but heroic altruism. Thus, reading a romantic scenario significantly increased men’s willingness to engage in heroic helping. For example, they indicated greater willingness to run into a burning building to save a trapped victim.[20] But they only insignificantly increased their willingness to engage in mundane helping. For example, it had little impact on their willingness to work at a homeless shelter.

Heroism displays friendship insurance reliability. This encourages all types of friendship reciprocity relationships, even romantic ones!

Footnotes:

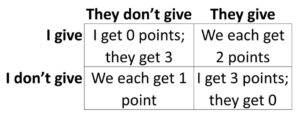

[1] Boyd, R. (1988). Is the repeated prisoner’s dilemma a good model of reciprocal altruism? Ethology and Sociobiology, 9(2-4), 211-222.

This is known as the iterated prisoner’s dilemma game. For example, two players both face these payoffs:

where each must choose before knowing what the other will do.

[2] Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1996). Friendship and the banker’s paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Proceedings of the British Academy, 88, 119-144.

[3] “Many nonhuman animals possess long-term cooperative social bonds that are functionally analogous to human friendships. Such long-term cooperative social bonds (henceforth – social bonds) are well described in chimpanzees and baboons (Seyfarth & Cheney, 2012), and there is also evidence for their existence in macaques, capuchin monkeys, elephants, feral horses, hyena, dolphins, bats, corvids, and mice (Braun & Bugnyar, 2012; Carter & Wilkinson, 2013c; Fraser & Bugnyar, 2012; Seyfarth & Cheney, 2012; Weidt, Hofmann, König, 2008; Weidt, Lindholm, & König, 2014). Field studies have demonstrated that strong social bonds provide clear fitness benefits (e.g., Cameron, Setsaas, & Linklater, 2009; Schülke, Bhagavatula, Vigilant, & Ostner, 2010; Silk et al., 2010).” Carter, G. (2014). The reciprocity controversy. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 1(3), 368-386. p. 374.

[4] Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1996). Friendship and the banker’s paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Proceedings of the British Academy, 88, 119-144.

[5] Id. 136-137.

[6] See previous article: The Power of Heroic Philanthropy: Understanding Donor Motivations

[7] Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1996). Friendship and the banker’s paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Proceedings of the British Academy, 88, 119-144. p. 136-137.

[8] (2016, June 2). Personal communication. ABA Law School Development Conference, San Diego, CA.

[9] “These ancient habits would induce modern humans to treat medical care as a way to show that you care. Medical care provided by our allies would reassure us of their concern.” Hanson, R. (2008). Showing that you care: The evolution of health altruism. Medical Hypotheses, 70(4), 724-742.

[10] Sugiyama, L. S., & Sugiyama, M. S. (2003). Social roles, prestige, and health risk. Human Nature, 14(2), 165-190. p. 168.

[11] Pudelek, J. (2014, July 10). Eleven characteristics of successful fundraisers revealed at IoF National Convention. Civil Society. https://www.civilsociety.co.uk/news/eleven-characteristics-of-successful-fundraisers-revealed-at-iof-national-convention.html

[12] Levine, N. B. (2019). From bankruptcy to billions: Fundraising the Naomi Levine way. Independently published. p. 31.

[13] CASE (Council for Advancement and Support of Education). (2013). Fundraising fundamentals. CASE. http://www.case.org/Publications_and_Products/Fundraising_

Fundamentals_Intro/Fundraising_Fundamentals_section_7/Fundraising_Fundamentals_section_73.html

[14] McCambridge, R. (2013, July 25). Naomi Levine: Insights from a master of fundraising. Nonprofit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/insights-from-a-master-naomi-levine-on-the-fundamentals-of-fundraising/

[15] Id.

[16] Kelly, S., & Dunbar, R. I. (2001). Who dares, wins. Human Nature, 12(2), 89-105.

[17] Id. p. 102.

[18] Steinman, J. (1983). Holding out for a hero [Recorded by B. Taylor]. On Faster than the speed of night [CD]. Columbia Records.

[19] Iredale, W., Van Vugt, M., & Dunbar, R. (2008). Showing off in humans: Male generosity as a mating signal. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(3), 386-392.

[20] Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., Sundie, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., Miller, G. F., & Kenrick, D. T. (2007). Blatant benevolence and conspicuous consumption: When romantic motives elicit strategic costly signals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 85-102.

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- How transactional donor relationships kill generosity

- Dr. James explains the power of giving: why leading with a gift always wins

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!